A Libertarian Vision for Poverty and Welfare

A libertarian world won’t eliminate all poverty, but it offers powerful tools for greatly reducing it, and improving the lives of the poorest and least privileged.

The stereotypes of libertarian attitudes toward the poor range from indifference to outright hostility. Yet a libertarian world would offer the poor a greater opportunity to escape poverty, become self-sufficient, and attain their full potential than does our current government-run social welfare system.

A libertarian approach to fighting poverty would be very different from our current one, which primarily consists of throwing money at the problem. This year, federal, state, and local governments will spend more than $1 trillion to fund more than 100 separate anti-poverty programs. 1 In fact, since Lyndon Johnson declared war on poverty 52 years ago, anti-poverty programs have cost us more than $23 trillion. 2 That’s a huge sum of money by any measure.

Although far from conclusive, the evidence suggests that this spending has successfully reduced many of the deprivations of material poverty. That shouldn’t be a big surprise. As George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen notes, under most classical economic theories, “a gift of cash always makes individuals better off.” 3 Regardless of how dim a view one takes of government competence in general, it would be virtually impossible for the government to spend $23 trillion without benefiting at least some poor people.

Yet it is impossible to walk through many poor neighborhoods, from inner cities to isolated rural communities, and think that our welfare system is working the way it should. These are areas where the government has spent heavily to reduce poverty. A high percentage of residents are receiving some form of government assistance. And as a result, the poor may well be better off financially than they would be in the absence of government aid. Yet no one could honestly describe those communities or the people living in them as thriving or flourishing in any sense of the word.

Perhaps The Economist put it best:

If reducing poverty just amounts to ushering Americans to a somewhat less meagre existence, it may be a worthwhile endeavor but is hardly satisfying. The objective, of course, should be a system of benefits that encourages people to work their way out of penury, and an economy that does not result in so many people needing welfare in the first place. Any praise for the efficacy of safety nets must be tempered by the realization that, for one reason or another, these folks could not make it on their own. 4

And therein lies the real failure of government anti-poverty efforts. Our efforts have been focused on the mere alleviation of poverty, making sure that the poor have food, shelter, and the like. That may be a necessary part of an anti-poverty policy, but it is far from sufficient. A truly effective anti-poverty program should seek not just to alleviate poverty’s symptoms but to eradicate the disease itself. We should seek to make sure not only that people are fed and housed, but also that they are able to rise as far as their talents can take them. In a sense, we focus too much on poverty and not enough on prosperity.

Attacking the Root Causes of Poverty

A libertarian approach to poverty would instead attack the underlying causes of poverty, including structural barriers to economic success.

Consider the criminal justice system, for example. Ample evidence indicates that overcriminalization and the abuses inherent in the U.S. criminal justice system contribute significantly to poverty. As President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers pointed out in 2016:

Having a criminal record or history of incarceration is a barrier to success in the labor market, and limited employment or depressed wages can stifle an individual’s ability to become self-sufficient. Beyond earnings, criminal sanctions can have negative consequences for individual health, debt, transportation, housing, and food security. Further, criminal sanctions create financial and emotional stresses that destabilize marriages and have adverse consequences for children. 5

Harvard’s William Julius Wilson—taking note of the nearly 1.5 million young African American men who have been rendered largely unmarriageable because of their involvement with the criminal justice system—has written extensively about the effect of criminal justice on nonmarital birthrates in poor communities. Conservatives are often quick to lecture poor women on the need to delay pregnancy until after marriage—and the evidence suggests that nonmarital childbearing can make it more difficult to escape poverty—but that begs the question of who poor women are supposed to marry. If large numbers of men in their communities cannot find work because of a criminal record or are simply not present because they are incarcerated, the likelihood of having children outside marriage increases dramatically.

Scholars at Villanova University found that our criminal justice policies have increased poverty by an estimated 20 percent. And another study found that a family’s probability of being poor is 40 percent greater if the father is imprisoned. Given that 5 million children have an imprisoned parent, that factor is an enormous contributor to poverty in America. 6

But a more libertarian society would end overcriminalization and dramatically reduce overincarceration. Ending the war on drugs, and legalizing other victimless activities from prostitution to gambling, would remove this enormous barrier to economic participation and self-sufficiency.

Education provides another example. Numerous studies show that educational success is a key determinant of poverty. 7 The days in which a person could drop out of school, head down to the local factory, and find a job that enabled him to support a family are long gone. Someone who drops out of school is five times more likely to be persistently in poverty before age 30 than someone who completes high school. 8

At the same time, government-run schools are doing an increasingly poor job of educating children, especially children who grow up in poverty. Studies have consistently shown that schools attended mostly by poor children have poorer records of educational achievement than schools attended by more affluent students. 9

Libertarian policies will break up the government education monopoly. Whether we are talking about taking incremental steps, such as charter schools, vouchers, and tuition tax credits, or more fully separating school and state, a libertarian approach to education would lead to more competition and innovation in educational alternatives and would give parents the ability to escape poorly performing schools.

Libertarian policies would also reduce the cost of living, especially for those with low incomes. For instance, trade barriers significantly raise the cost of many basic goods that make up a large portion of the poor’s budget. Tariffs levied on shoes and clothing alone cost the average household in the poorest quintile $92 a year, and those with children often pay far more. 10

Zoning and land-use policies can add as much as 40 percent to the cost of housing in some cities. 11 In neighborhoods like New York’s Manhattan, the zoning tax is even higher, at 50 percent or more. And these regulations are thought to affect far more than just housing prices: geographic mobility, economic and racial integration, and economic growth are all affected negatively. Libertarians would eliminate these costly regulations that make it difficult for the poor to afford basic goods and services.

Most important, libertarian policies would lead to more rapid economic growth and would ensure that the benefits of that growth were spread more inclusively. As President Obama once pointed out, “The free market is the greatest producer of wealth in history—it has lifted billions of people out of poverty.” 12 By reducing taxes and regulations, libertarians would spur economic growth, increasing the overall wealth in society.

But to really raise the poor out of poverty, we must ensure that they can fully participate in the opportunities that a growing economy provides. Here again, libertarian policies would benefit the poor by removing barriers to economic participation. For example, an estimated 40 percent of professions in the United States currently require some form of government license to practice. That includes more than 1,100 different professions requiring a license in at least one state—from florists to funeral attendants, from tree trimmers to makeup artists. 13 Removing licensure barriers not only unlocks employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for the poor in low-skill occupations, but also lowers prices in industries such as health care where occupational licensure restricts competition.

Effective Charity

Of course, even if all the reforms discussed above were completely successful, some people would still be unable to become fully self-sufficient. A libertarian world would support a vigorous network of private charity to assist them.

Charity works where government does not for a variety of reasons. For one thing, private charities can better individualize their approach to the circumstances of the poor in ways that a government program can never do. For reasons both legal and bureaucratic, government regulations must be designed in ways that treat all similarly situated recipients alike. As a result, most government programs rely on the simple provision of cash or in-kind goods and services without any attempt to differentiate the specific needs or circumstances of individual recipients.

Do individuals have family problems or mental health issues? Do they lack job skills or have a criminal record? What prevents them from becoming self-supporting? Administrators of government programs seldom know or care. And even if they did, they must still respond with a one-size-fits-all answer.

Private charities are also much better at directing assistance to those who need it most. That ability is not just a question of efficiency, although relatively few successful charities have the burdensome bureaucratic infrastructure of government programs. Rather, private charities have the discretion necessary to focus their assistance where it will do the most good. Private charity is also more likely to target short-term emergency relief, rather than long-term support. Consequently, it can both better address a crisis and avoid problems of dependency.

To the degree that poverty results from individual choices and behavior, private charities can demand a change in behavior in exchange for aid. For example, a private charity may withhold funds if a recipient doesn’t stop using alcohol or drugs, doesn’t get a job, or gets pregnant. For any number of reasons, we don’t want the government to adopt such paternalistic measures, but private charities have proven effective when they do so. 14

Governments lack the knowledge of individual circumstances that would enable them to intervene in matters of individual behavior. Moreover, paternalistic interventions inevitably run headlong into divisive cultural issues. Allowing government to enforce particular points of view on such issues is questionable on ethical grounds and a certain recipe for political conflict. And charities are better at scaling up or down in response to particular needs or issues, whereas government bureaucracies inevitably seek to continue or expand their mission.

Finally, private charity builds an important bond between giver and receiver. For recipients, private charity is not an entitlement, but a gift carrying reciprocal obligations. But more important, private charity demands that donors become directly involved. It is easy to be charitable with someone else’s money. As Robert Thompson of the University of Pennsylvania noted a century ago, using government money for charitable purposes is a “rough contrivance to lift from the social conscience a burden that should not be either lifted or lightened in any way.” 15

Can Charity Be Provided Voluntarily?

Americans are an amazingly generous people. In 2015, we donated $373 billion to charity. Roughly $265 billion of that, or fully 71 percent, was given by individuals (the rest came from corporations, foundations, and other organizations). 16 More than 83 percent of adult Americans make some charitable contribution each year. 17 True, a substantial portion of that giving went to entities like universities, hospitals, and the arts, rather than to direct human services to the poor. But even so, Americans voluntarily gave tens of billions of dollars to help the poor.

And it wasn’t just money. We also donated more than 3.2 million hours of our time. Roughly 65 percent of Americans perform some form of volunteer work. And that doesn’t include the countless hours given to help friends, family members, neighbors, and others outside the formal charity system.

Still, if we reduced or eliminated government welfare spending, would there be enough charity to meet the needs of the poor? The numbers provide a reason for concern: as much as Americans give, that amount currently falls well short of the nearly $1 trillion that federal, state, and local governments spend on anti-poverty programs. 18

But that fact ignores evidence suggesting that, in the absence of government welfare programs, private charitable giving will almost certainly increase. Numerous studies have documented a “displacement effect,” whereby government programs crowd out private giving. 19

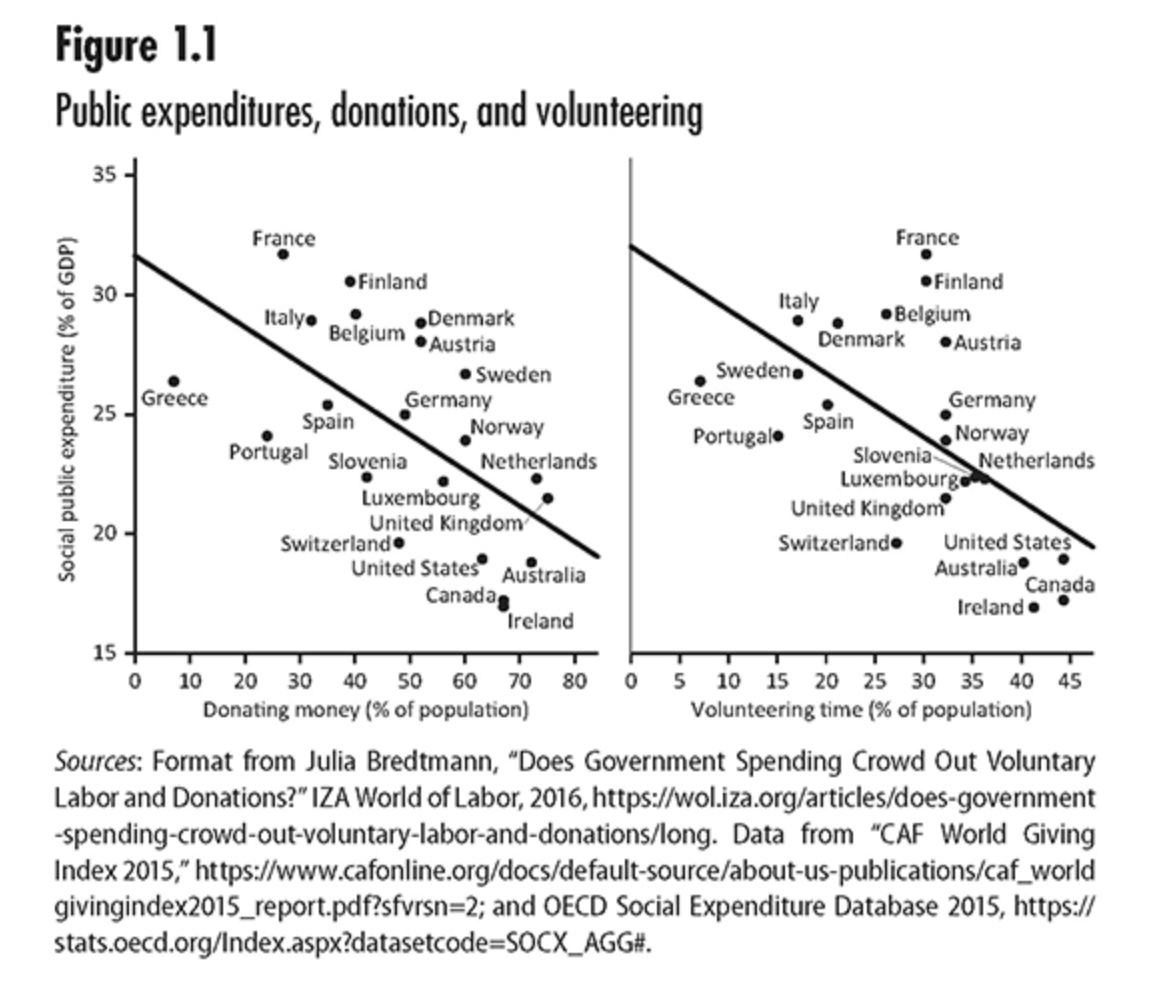

For example, a comparison of charitable giving across countries confirms the finding that government welfare spending reduces private charitable efforts. Among rich countries, those with lower social expenditures as a share of the economy see a higher portion of their population donate to charity. Moreover, people in countries with a smaller welfare state are also more likely to volunteer (see Figure 1.1).

History suggests that people intuitively respond to greater levels of need with higher levels of giving. Charitable giving, which had risen steadily from the end of World War II until the mid-1960s, declined dramatically in the wake of the Great Society. In the 1980s, when the rise in welfare spending began to flatten out (and, not coincidentally, the public was deluged with media stories warning of cutbacks to social welfare programs), the public responded with increased private giving. 20

Economists Jonathan Meer, David Miller, and Elisa Wulfsberg find that levels of giving fell after the most recent recession even after considering the giver’s individual economic situation. Moreover, Meer and his colleagues point out that this shift could portend a broader change in attitude toward charitable giving. 21 Of course, this effect might be a one-time response to the unusual circumstances surrounding this recession. But since charitable habits are hard to break once formed, it is something to keep an eye on. 22

Giving and Civil Society

True charity is ennobling of everyone involved, both those who give and those who receive. A government grant is ennobling of no one. Alexis de Tocqueville recognized this point more than 150 years ago when he called for the abolition of public relief, citing the fact that private charity established a “moral tie” between giver and receiver. That tie is destroyed when the money comes from an impersonal government grant. The donors (taxpayers) resent their involuntary contribution, while the recipients feel no real gratitude for what they receive.

As a matter of policy, therefore, it would be preferable to shift as much of the burden of caring for the poor as possible to private charities. Doing so would avoid the pitfalls of coercive redistribution and the bureaucratic failures of traditional welfare.

The total dollar amount spent on charity, both private and public, is secondary to the effectiveness of each dollar spent. Well-functioning institutions of civil society like churches and other associational organizations may have significantly greater bang for their buck than government spending.

Utah provides an instructive example here. The state government spends relatively little on social welfare compared with other states, yet Utah has one of the lowest poverty rates and the highest rate of upward mobility among the states. 23 Behind Utah’s success in caring for its least well off is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS).

In response to the failures of New Deal relief during the Great Depression, the LDS church established a well-coordinated yet highly decentralized network for the purpose of delivering aid to LDS adherents. Heber Grant, an LDS leader, described the aim of this effort: “To set up insofar as it might be possible, a system under which the curse of idleness would be done away with, the evils of a dole abolished and independence, industry, thrift and self-respect be once more established among our people. The aim of the Church is to help the people to help themselves. Work is to be re-enthroned as the ruling principle of the lives of our Church membership.” 24

To remain in good standing within the church, Mormons must contribute at least 10 percent of their income to the church, a portion of which goes to supporting a safety net for Mormons who fall on hard times. Mormons are also strongly encouraged to volunteer and provide a “fast offering,” which is the dollar equivalent of two meals per month.

And although funds and labor are no doubt important, the true strength of the Mormon safety net lies in the cultivation of deep interpersonal bonds among LDS members. For instance, the ministering program requires every Mormon to offer regular counseling and support to sometimes as many five families. Such personal connections are the greatest advantage that private charitable efforts have over those run by the state. This approach allows assistance to be tailored specifically to an individual’s needs and to deliver the emotional support government welfare can’t buy.

Charity premised on voluntary associations rather than government coercion has not been solely the domain of religious institutions. During the first part of the 20th century, African Americans were generally excluded from government social welfare programs. Black lodges, such as the Prince Hall Masons, and other institutions established a wide-ranging and highly successful charitable network. They built orphanages and old-age homes, provided food to the hungry and shelter to the homeless, and helped the unemployed find work. Black lodges also provided medical care, hiring physicians to treat members and their families. Known as “lodge-practice medicine,” the networks were so extensive that African Americans were more likely than whites to have some form of health insurance than were whites during the early years of the 20th century. 25 (Unfortunately, those private African American charitable networks were squeezed simultaneously by racism on one side and by the growing welfare state on the other. Today, they have largely faded away.)

Emerging technologies offer additional opportunities to restore the civil society bonds that are a precondition to effective charity. In particular, blockchain technology enables individuals to give directly to the needy without relying on any third party. At its most basic, a blockchain is a decentralized platform that can be used to transfer money electronically. Because all blockchain transactions are verified on a transparent ledger via a decentralized network of computers, users can be confident that their transfers are secure. Yet the possibilities that blockchain technology creates for charitable innovation are enormous. For instance, donors may choose to write conditions to blockchain transactions to ensure that charitable funds are well spent. Such preconditions might include requiring that individuals purchase only healthy foods or attend religious services. For donors, such requirements restore the basic sense of accountability that is necessary to prompt voluntary generosity. At the same time, recipients benefit from being nudged to integrate with civil society institutions and build productive interpersonal relationships.

Of course, even with increased charitable giving, we may never completely eliminate the need for a government safety net. But we should recognize the important role that private charity fulfills, and we should lean, whenever possible, in that direction.

Freeing Charity

Libertarians would also remove government-imposed barriers to private charity. For example, Wilmington, North Carolina, passed an ordinance that prohibits sharing food on city streets and sidewalks. And Las Vegas bans “the providing of food or meals to the indigent for free or for a nominal fee” in city parks. Similarly, Orlando, Florida, prohibits sharing food with more than 25 people in city parks without a permit and limits groups to doing so twice a year. Atlanta mandates that all aid to the homeless must pass through one of eight municipally approved organizations. Baltimore requires organizations to obtain a food service license before feeding the homeless. And so on. 26

Moreover, numerous states have prevented doctors from providing free medical care to the poor because those physicians are not licensed in the state. For example, in the aftermath of tornadoes that devastated Joplin, Missouri, the Tennessee-based organization Remote Area Medical, which provides free medical care, was blocked from providing free eyeglasses to the victims. 27 And New York State blocked Remote Area Medical from providing free health care services to the poor because the group uses mobile rather than fixed facilities. 28

Other municipalities have used zoning ordinances to block homeless shelters. For instance, in several cities, zoning laws prohibit churches from operating homeless shelters on their property. 29

When charities and the needs of the poor run into entrenched special interests that can use government power to achieve their desires, the charities are all too often the losers. In a more libertarian world, private charity would have much more latitude.

Less Poverty in a Libertarian World

We can expect libertarian policies to significantly reduce poverty and increase the ability of the poor to become self-sufficient, full participants in a growing economy. Even if libertarian reforms have only a small immediate effect, we should expect an altered landscape to affect future generations substantially. Thus, what would begin as a small wedge of increased self-sufficiency would steadily widen as the children of the poor have an opportunity to grow up under very different circumstances. Ideally, intergenerational mobility would also increase. The curve may start to bend today, but the biggest effect will be in the future. The number of people in need of government assistance will, it is hoped, be much smaller than it is today.

At the same time, a libertarian world would unleash the full potential of private charity. Those charitable efforts not only would be more effective, but would be focused on a much smaller population. Can we guarantee that libertarian policies will eliminate poverty? Of course not. Utopia is not an option. But we can provide for the poor effectively—more effectively than current policies. Shifting from government welfare to private action should not—and does not—mean turning our backs on the poor. It does mean finding a better way to help them.

1. Michael D. Tanner, “The American Welfare State: How We Spend Nearly $1 Trillion a Year Fighting Poverty—And Fail,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 694, April 11, 2012.

2. Rachel Sheffield and Robert Rector, “The War on Poverty after 50 Years,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder no. 2955, September 15, 2014.

3. Tyler Cowen, “Does the Welfare State Help the Poor?” Social Philosophy and Policy 19, no. 1 (2002): 39.

4. S. M., “Are We Helping the Poor?” The Economist, December 18, 2013.

5. Council of Economic Advisors, “Economic Perspectives on Incarceration and the Criminal Justice System,” April 2016, p. 45.

6. Council of Economic Advisors, p. 5.

7. See, for example, Michael Greenstone et al., “Thirteen Economic Facts about Social Mobility and the Role of Education,” The Hamilton Project policy memo, June 2013.

8. U.S. Census Bureau, “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2016,” Table 3.

9. See, for example, Reyn van Ewijik and Peter Sleegers, “The Effect of Peer Socioeconomic Status on Student Achievement,” Education Research Review 5, no. 1 (June 2011): 134–50; Robert Putnam, Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), p. 165.

10. Ryan Bourne, “Government and the Cost of Living: Income-Based vs. Cost-Based Approaches to Alleviating Poverty,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 847, September 4, 2018.

11. Edward L. Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko, “The Impact of Building Restrictions on Housing Affordability,” Economic Policy Review 9, no. 2 (June 2003): 21–39.

12. Robert deFina and Lance Hannon, “The Impact of Mass Incarceration on Poverty,” Journal of Crime and Delinquency 59, no. 4 (June 2013): 562–86.

13. Council of Economic Advisers, “Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers,” July 2015.

14. See, for example, Marvin Olasky, The Tragedy of American Compassion (New York: Free Press, 1986).

15. Robert Ellis Thompson, Divine Order of Human Society: Being the L. P. Stone Lectures for 1891, Delivered in Princeton Theological Seminary (Philadelphia: J. D. Wattles, 1891), p. 246.

16. “Giving USA 2016: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2015,” Giving USA, Chicago.

17. “Most Americans Practice Charitable Giving, Volunteerism,” Gallup Inc., Washington, December 13, 2013.

18. Tanner, “American Welfare State.”

19. See, for example, Russell Roberts, “A Positive Model for Private Charity and Public Transfers,” Journal of Political Economy 92, no. 1 (February 1984): 2136–48.

20. Charles Murray, In Pursuit: Of Happiness and Good Government (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), pp. 275–76.

21. Jonathan Meer, David Miller, and Elisa Wulfsberg, “The Great Recession and Charitable Giving,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 22902, December 2016.

22. Meer, Miller, and Wulfsberg, “Charitable Giving.”

23. Megan McArdle, “How Utah Keeps the American Dream Alive,” Bloomberg Opinion, March 28, 2017.

24. “One Hundred Seventh Semi-Annual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints,” October 1936, p. 3.

25. David Beito, From Mutual Aid to the Welfare State: Fraternal Societies and Social Services, 1890–1967 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

26. See, for example, “Feeding Intolerance: Prohibitions on Sharing Food with People Experiencing Homelessness,” National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty and National Coalition on Homelessness, November 2007.

27. John K. Ross, “Missouri Still Forbids Free Health Care from Outside State,” Reason, August 6, 2013.

28. Jeff Reicert, “Dear New York Uninsured: Screw You, Love Governor Cuomo,” Huffington Post, January 19, 2015.

29. Richard R. Hammer, “Zoning Laws and Homeless Shelters,” Church Law & Tax Report, March/April 1995.