Why Did the Southern States Secede?

It shouldn’t need to be said, but the Confederacy didn’t stand for opposing federal overreach or eliminating handouts to big business--it stood for slavery.

It has long been conventional wisdom among certain libertarians and classical liberal historians that the southern Confederacy was a great bastion of Jeffersonianism. In the South, many twentieth-century libertarians thought they had found a political culture supporting free trade (especially through low tariffs) and limited government (using the vehicle of “States’ Rights”). This view, however, ultimately rests on a privileged selection of the evidence and a good deal of historical forgetfulness, most likely the result of twentieth-century history more so than anything from the nineteenth. To correct such mistakes, we will examine in depth the documents through which southern states proclaimed themselves free and independent of the Union government to discover the reasons they themselves offered for doing so. While most states in the Confederacy simply passed Ordinances of Secession, South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia passed additional “Declarations of Causes,” offering invaluable insight into the conventions’ political machinations and motivations. As the first state to secede, South Carolina’s “Declarations” established precedent and unabashedly claimed that the primary reason for secession remained the refusal of northern states to comply with the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott (1857) decision.

Introduction

South Carolina

We begin with South Carolina’s explanation of the legal and historical basis for state secession, emphasizing the existence of the states as prior to the existence of the Union, which was in fact a new government created by thirteen sovereign and independent states. In creating this government, South Carolina declared, the states did not transfer their sovereignty and retained the right to dissolve the compact:

The people of the State of South Carolina, in Convention assembled, on the 26th day of April, A.D., 1852, declared that the frequent violations of the Constitution of the United States, by the Federal Government, and its encroachments upon the reserved rights of the States, fully justified this State in then withdrawing from the Federal Union; but in deference to the opinions and wishes of the other slaveholding States, she forbore at that time to exercise this right. Since that time, these encroachments have continued to increase, and further forbearance ceases to be a virtue…

After their unanimous declaration of independence in 1776, thirteen sovereign and independent new states assumed their positions among fellow nations of the world. By 1783, these new countries had formed a confederated government in which each party retained sovereignty. In the Treaty of Paris, King George III recognized each former colony as a separate belligerent, the sovereignty of each now internationally undisputed.

In 1787, Deputies were appointed by the States to revise the Articles of Confederation, and on 17th September, 1787, these Deputies recommended for the adoption of the States, the Articles of Union, known as the Constitution of the United States.

The parties to whom this Constitution was submitted, were the several sovereign States…

Despite the persistence of Neo-Confederate myths about the alleged prevalence of Jeffersonian political philosophy, southern intellectual and political culture gradually (though often in the form of punctuated equilibrium) shed Jefferson’s key premises of natural law and rights for several decades before the Civil War. Southerners developed in its place an indigenous form of political pragmatism based in the sovereignty of individual states. It is perhaps most important to note that the shift from natural law to “states’ rights” arguments that characterized southern political life, ca. 1800-1860, implied the denial of the universal sovereignty of individuals while upholding the sovereignty of constituted governments. As the state governments were the parties to the Constitution (neither the “whole people” nor the Union created or ratified the Constitution), state governments were bound to honor the compact. South Carolina charges, however, that frequent northern-state refusals to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act have effectively nullified the constitutional contract which bound the states. It was, therefore, a formality for South Carolina to declare herself independent.

In the present case, that fact is established with certainty. We assert that fourteen of the States have deliberately refused, for years past, to fulfill their constitutional obligations [with respect to the Fugitive Slave Clause and Fugitive Slave Act of 1850]…

For many years these laws were executed. But an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery, has led to a disregard of their obligations, and the laws of the General Government have ceased to effect the objects of the Constitution. The States of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa, have enacted laws which either nullify the Acts of Congress or render useless any attempt to execute them. In many of these States the fugitive is discharged from service or labor claimed, and in none of them has the State Government complied with the stipulation made in the Constitution…

Those States have assume the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions; and have denied the rights of property established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution; they have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery; they have permitted open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace and to eloign the property of the citizens of other States. They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection.

It is not the tariff, not the erosion of state authority in the face of a federal juggernaut, not the safety of Jeffersonian republicanism against Lincolnian Leviathan which prompted South Carolinian secession. Clearly and undoubtedly, South Carolina identified the failure of northern states to abide by the national Fugitive Slave Act as the primary motivating factor for secession, especially given the recent (1860) rise to power of a political party committed to keeping the national territories free of slavery. Lincoln was elected without a single vote from the South (in most southern states the Republican Party did not appear on ballots), and nothing signaled the death of southern (or slaveholding) power within the Union more than the election of a president without even consulting southern opinion on the matter. The South Carolina declaration concluded:

For twenty-five years this agitation has been steadily increasing, until it has now secured to its aid the power of the common Government. Observing the *forms* of the Constitution, a sectional party has found within that Article establishing the Executive Department, the means of subverting the Constitution itself. A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery. He is to be entrusted with the administration of the common Government, because he has declared that that “Government cannot endure permanently half slave, half free,” and that the public mind must rest in the belief that slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction.

This sectional combination for the submersion of the Constitution, has been aided in some of the States by elevating to citizenship, persons who, by the supreme law of the land, are incapable of becoming citizens; and their votes have been used to inaugurate a new policy, hostile to the South, and destructive of its beliefs and safety.

On the 4th day of March next, this party will take possession of the Government. It has announced that the South shall be excluded from the common territory, that the judicial tribunals shall be made sectional, and that a war must be waged against slavery until it shall cease throughout the United States.

The guaranties of the Constitution will then no longer exist; the equal rights of the States will be lost. The slaveholding States will no longer have the power of self-government, or self-protection, and the Federal Government will have become their enemy.

Georgia

When Georgia proclaimed its independence and, in keeping with American tradition, listed its grievances against the Union government, it also noted the overriding and primary importance of protecting slavery over all else. Importantly, Georgia’s declaration noted first the influence and impact of northern abolitionists both on national politics and the potential security of southern society, continuing to highlight proslavery themes in the pattern established by South Carolina:

For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery. They have endeavored to weaken our security, to disturb our domestic peace and tranquility, and persistently refused to comply with their express constitutional obligations to us in reference to that property, and by the use of their power in the Federal Government have striven to deprive us of an equal enjoyment of the common Territories of the Republic…The party of Lincoln, called the Republican party, under its present name and organization, is of recent origin. It is admitted to be an anti-slavery party. While it attracts to itself by its creed the scattered advocates of exploded political heresies, of condemned theories in political economy, the advocates of commercial restrictions, of protection, of special privileges, of waste and corruption in the administration of Government, anti-slavery is its mission and its purpose. By anti-slavery it is made a power in the state…

Georgia’s “Declaration” built upon the South Carolina example by examining in-depth the methods by which northerners had used the national government to exploit the South. To many, such arguments have been evidence of southern beliefs in the principles of free markets, limited government, and a free society. Such a reading of southern history, however, fails to account for the way in which anti-Union arguments were ultimately subsidiary to pro-slavery arguments. In no way could we consider the southern or Confederate project as an extension of Jeffersonian, essentially libertarian, principles:

The material prosperity of the North was greatly dependent on the Federal Government; that of the South not at all. In the first years of the Republic the navigating, commercial, and manufacturing interests of the North began to seek profit and aggrandizement at the expense of the agricultural interests. Even the owners of fishing smacks sought and obtained bounties for pursuing their own business (which yet continue), and $500,000 is now paid them annually out of the Treasury. The navigating interests begged for protection against foreign shipbuilders and against competition in the coasting trade.

Congress granted both requests, and by prohibitory acts gave an absolute monopoly of this business to each of their interests, which they enjoy without diminution to this day. Not content with these great and unjust advantages, they have sought to throw the legitimate burden of their business as much as possible upon the public; they have succeeded in throwing the cost of light-houses, buoys, and the maintenance of their seamen upon the Treasury…

The manufacturing interests entered into the same struggle early, and has clamored steadily for Government bounties and special favors..and they received for many years enormous bounties by the general acquiescence of the whole country.

But when these reasons ceased they were no less clamorous for Government protection, but their clamors were less heeded— the country had put the principle of protection upon trial and condemned it. After having enjoyed protection to the extent of from 15 to 200 per cent. upon their entire business for above thirty years, the act of 1846 was passed. It avoided sudden change, but the principle was settled, and free trade, low duties, and economy in public expenditures was the verdict of the American people. The South and the Northwestern States sustained this policy. There was but small hope of its reversal; upon the direct issue, none at all.

Yes, the document complained that northerners had long used their disproportionate power in the House of Representatives to forcibly and unconstitutionally channel wealth from the South northward. Yes, Georgia noted the corrupting influence of moneyed and business interests on northern politics. Yes, the secessionists singled out the tariff as a key indicator of northern power and the will to exploit southerners. But as Georgia recognized, the South gradually won each of those issues, culminating in the anti-protectionist Walker Tariff of 1846. It was only then that the economic and political interests throughout the North began looking for a new cause to agitate:

All these classes saw this and felt it and cast about for new allies. The anti-slavery sentiment of the North offered the best chance for success…We had acquired a large territory by successful war with Mexico; Congress had to govern it; how, in relation to slavery, was the question then demanding solution. This state of facts gave form and shape to the anti-slavery sentiment throughout the North and the conflict began. Northern anti-slavery men of all parties asserted the right to exclude slavery from the territory by Congressional legislation and demanded the prompt and efficient exercise of this power to that end. This insulting and unconstitutional demand was met with great moderation and firmness by the South. We had shed our blood and paid our money for its acquisition; we demanded a division of it on the line of the Missouri restriction or an equal participation in the whole of it. These propositions were refused, the agitation became general, and the public danger was great. The case of the South was impregnable. The price of the acquisition was the blood and treasure of both sections— of all, and, therefore, it belonged to all upon the principles of equity and justice…

It was, in sum, the combination of classic northern Clay-Lincoln Whigs and long-time antislavery activists from across the entire political spectrum into a single great (and successful) antislavery party that prompted Georgia’s secession, and decidedly not Lincoln’s position on the tariff or other questions of economic liberty. Because the ruling party (as of Lincoln’s election) refused to recognize the legitimacy of property in slaves in the national territories and half of the states, the southern political class resolved to secede and establish a nation of their own, specifically dedicated to protecting the most special of all special interests in the region, property in slaves:

This is the party to whom the people of the North have committed the Government. They raised their standard in 1856 and were barely defeated. They entered the Presidential contest again in 1860 and succeeded…

The prohibition of slavery in the Territories is the cardinal principle of this organization.

For forty years this question has been considered and debated in the halls of Congress, before the people, by the press, and before the tribunals of justice. The majority of the people of the North in 1860 decided it in their own favor. We refuse to submit to that judgment, and in vindication of our refusal we offer the Constitution of our country and point to the total absence of any express power to exclude us…

The people of Georgia have ever been willing to stand by this bargain, this contract; they have never sought to evade any of its obligations; they have never hitherto sought to establish any new government; they have struggled to maintain the ancient right of themselves and the human race through and by that Constitution. But they know the value of parchment rights in treacherous hands, and therefore they refuse to commit their own to the rulers whom the North offers us. Why? Because by their declared principles and policy they have outlawed $3,000,000,000 of our property in the common territories of the Union; put it under the ban of the Republic in the States where it exists and out of the protection of Federal law everywhere; because they give sanctuary to thieves and incendiaries who assail it to the whole extent of their power, in spite of their most solemn obligations and covenants; because their avowed purpose is to subvert our society and subject us not only to the loss of our property but the destruction of ourselves, our wives, and our children, and the desolation of our homes, our altars, and our firesides…

Mississippi

Mississippi left virtually no room to mistake her purposes in seceding from the United States, declaring that slavery, particularly slavery of “the black race,” is decreed by “nature” and in fact perfectly consonant with naturalistic, scientifically-informed and realistic views of the modern industrial economy.

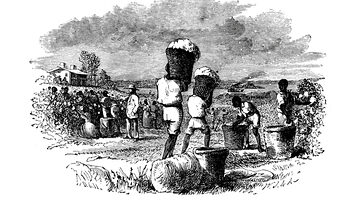

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery— the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution, and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.

That we do not overstate the dangers to our institution, a reference to a few facts will sufficiently prove.

It has grown until it denies the right of property in slaves, and refuses protection to that right on the high seas, in the Territories, and wherever the government of the United States had jurisdiction.

It refuses the admission of new slave States into the Union, and seeks to extinguish it by confining it within its present limits, denying the power of expansion.

It tramples the original equality of the South under foot.

It has nullified the Fugitive Slave Law in almost every free State in the Union, and has utterly broken the compact which our fathers pledged their faith to maintain.

It advocates negro equality, socially and politically, and promotes insurrection and incendiarism in our midst.

Radical abolitionists from David Walker to John Brown and Lysander Spooner worked diligently for decades to disrupt and revolutionize southern slave society. Only the ascension of the Republican Party to national power provided them sufficient legal and military cover to seriously challenge slavery’s existence.

It has recently obtained control of the Government, by the prosecution of its unhallowed schemes, and destroyed the last expectation of living together in friendship and brotherhood.

Utter subjugation awaits us in the Union, if we should consent longer to remain in it. It is not a matter of choice, but of necessity. We must either submit to degradation, and to the loss of property worth four billions of money, or we must secede from the Union framed by our fathers, to secure this as well as every other species of property. For far less cause than this, our fathers separated from the Crown of England.

Texas

Texas, of course, had the distinction of being the sole sister-republic to join the Union by treaty--a fact of critical importance to Texas’ compact theory of the Union. Regardless of the legal propriety of Texas’ secession, the Texan “Declaration’s” reasons for embracing secession as more than a theoretical possibility are rooted in the same racist fears for the future of slavery as the previous declarations:

Texas…was received into the confederacy with her own constitution, under the guarantee of the federal constitution and the compact of annexation, that she should enjoy these blessings. She was received as a commonwealth holding, maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery— the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits— a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time. Her institutions and geographical position established the strongest ties between her and other slave-holding States of the confederacy. Those ties have been strengthened by association. But what has been the course of the government of the United States, and of the people and authorities of the non-slave-holding States, since our connection with them?

The controlling majority of the Federal Government, under various pretences and disguises, has so administered the same as to exclude the citizens of the Southern States, unless under odious and unconstitutional restrictions, from all the immense territory owned in common by all the States on the Pacific Ocean, for the avowed purpose of acquiring sufficient power in the common government to use it as a means of destroying the institutions of Texas and her sister slaveholding States…

The States of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, Michigan and Iowa, by solemn legislative enactments, have deliberately, directly or indirectly violated the 3rd clause of the 2nd section of the 4th article [i.e. the fugitive slave clause] of the federal constitution, and laws passed in pursuance thereof; thereby annulling a material provision of the compact…

Texas follows Mississippi in maintaining the naturalism and scientific righteousness of “their beneficent and patriarchal system of African slavery.” According to the Texas “Declaration,” northerners erred in “proclaiming the debasing doctrine of equality of all men, irrespective of race or color— a doctrine at war with nature, in opposition to the experience of mankind, and in violation of the plainest revelations of Divine Law.” In the final estimation of the state of Texas, the Republican ascension to power was once again the primary motivating factor in recommending immediate secession from the Union. Republican power signaled northern willingness to protect abolitionist agitators throughout the Union while restricting slavery to its current borders:

They have for years past encouraged and sustained lawless organizations to steal our slaves and prevent their recapture, and have repeatedly murdered Southern citizens while lawfully seeking their rendition.

They have invaded Southern soil and murdered unoffending citizens, and through the press their leading men and a fanatical pulpit have bestowed praise upon the actors and assassins in these crimes, while the governors of several of their States have refused to deliver parties implicated and indicted for participation in such offenses, upon the legal demands of the States aggrieved.

They have, through the mails and hired emissaries, sent seditious pamphlets and papers among us to stir up servile insurrection and bring blood and carnage to our firesides.

They have sent hired emissaries among us to burn our towns and distribute arms and poison to our slaves for the same purpose.

They have impoverished the slave-holding States by unequal and partial legislation, thereby enriching themselves by draining our substance.

Notice that this previous statement is the first and only time one of the seceding states has cited economic exploitation by the North in isolation from the slavery issue as a reason for seceding. Yet, nestled as it is in a bed of proslavery justifications for secession, it hardly serves as a sufficiently libertarian reason to support the Confederate project.

They have refused to vote appropriations for protecting Texas against ruthless savages, for the sole reason that she is a slave-holding State.

Lincoln’s victory, once again, was the final blow to southern safety within the Union:

In view of these and many other facts, it is meet that our own views should be distinctly proclaimed.

We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable.

That in this free government *all white men are and of right ought to be entitled to equal civil and political rights;* that the servitude of the African race, as existing in these States, is mutually beneficial to both bond and free, and is abundantly authorized and justified by the experience of mankind, and the revealed will of the Almighty Creator, as recognized by all Christian nations; while the destruction of the existing relations between the two races, as advocated by our sectional enemies, would bring inevitable calamities upon both and desolation upon the fifteen slave-holding states.

Virginia

In fact, at the very end of our survey of “Declarations of Causes,” only Virginia’s refused to dwell on the subject of slavery. Virginia does not spend ink justifying slavery, nor deprecating the rights of Africans or African Americans--that only whites had rights in Virginia was simply assumed. Rather, the document’s focus is on the unconstitutional actions of the Lincoln administration and the resultant nullification of the federal compact. It is the compact theory of the Union boiled to a point, rigidly applied to a serious situation confronting Virginians, employed only after political means of resolving the sectional conflict clearly failed to resolve the fundamental conflict between northern “Free Society” and southern “Slave Society.”

The people of Virginia…having declared that the powers granted under the said Constitution were derived from the people of the United States, and might be resumed whensoever the same should be perverted to their injury and oppression; and the Federal Government, having perverted said powers, not only to the injury of the people of Virginia, but to the oppression of the Southern Slaveholding States.

Now, therefore, we, the people of Virginia, do declare and ordain that the Union between the State of Virginia and the other States under the Constitution aforesaid, is hereby dissolved, and that the State of Virginia is in the full possession and exercise of all the rights of sovereignty which belong and appertain to a free and independent State. And they do further declare that the said Constitution of the United States of America is no longer binding on any of the citizens of this State.

While discussions of the future safety of slavery dominated the Virginia secession convention throughout the Spring of 1861, fretful worrying about slavery’s future turned to fearful reaction after Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for volunteers to invade the Confederacy. By then, what appeared to many Virginians as yet another deeply divisive, but eminently compromisable political problem transmogrified into a consolidationist-abolitionist invasion of the South. The Virginia “Declaration,” therefore, well represents what has been called “The Myth of the Lost Cause,” the notion that secession was really all about maintaining classic, Jeffersonian, liberal government in the face of Leviathan-from-the-North. Yet even lurking behind Virginia’s rather tame proclamation were fears of slave rebellion and class revolution against planters in particular and white southerners more broadly. Even when the Old Dominion slowly rose to the occasion, she did so to defend slavery from the constant stream of abolitionist threats to southern social order.

Conclusion

While libertarians are often anxious to find a hero among a sea of bad actors in the Civil War period, I would suggest that we are on far better ground in asserting that neither the Union nor the Confederate governments actually represented the interests and wills of the average northern or southern Americans, much less the views of we modern libertarians (or even our closest contemporary ancestors, the Loco-Focos). Both sides, in fact, sought to use the force and power of the national government to defend special, sectional interests and fought a horrifyingly destructive war to protect powerful, quickly-centralizing nation-states: one built on finance capital and industry, one built on finance capital and plantation slavery. While there were indeed plenty of heroes alive in the antebellum and Civil War eras, we should not delude ourselves into thinking that Lincoln’s main enemies were necessarily our own friends.

Selected Bibliography

Banning, Lance. The Jeffersonian Persuasion: Evolution of a Party Ideology. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1978.

Bensel, Richard. Yankee Leviathan: The Origins of Central State Authority in America, 1859-1877. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1990.

Brugger, Robert. Beverly Tucker: Heart Over Head in the Old South. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 1978.

Burin, Eric. Slavery and the Peculiar Solution: A History of the American Colonization Society. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005.

Channing, Steven. Crisis of Fear: Secession in South Carolina. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1970.

Coussons, John Stafford. “Thirty Years with Calhoun, Rhett, and the Charleston Mercury: A Chapter in South Carolina Politics.” Ph.D. Dissertation. Louisiana State University, 1971.

Davis, Jefferson. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1881.

Dew, “Apostles of Secession,” North and South 4, No. 4 (April 2001): 24-38.

Horsman, Reginald. Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Eaton, Clement. Freedom of Thought in the Old South. Durham: Duke University Press. 1940.

Eaton, Clement. The Mind of the Old South. Louisiana State University Press. 1964.

Ericson, David. The Debate Over Slavery: Antislavery and Proslavery Liberalism in Antebellum America. New York: New York University Press. 2000.

Finkelman, Paul, ed. Defending Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Old South, A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s. 2003.

Freehling, William. The Road to Disunion, Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

Freehling, William. The Road to Disunion, Vol. II: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2007.

Hummel, Jeffrey Rogers. Emancipating Slaves, Enslaving Free Men: A History of the American Civil War. Chicago: Open Court, 1996.

Ingersoll, Thomas. Mammon and Manon in Early New Orleans: The First Slave Society in the Deep South, 1716-1819. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1999.

Krohn, Raymond. “Antebellum South Carolina Reconsidered: The Libertarian World of Robert J. Turnbull.” The Journal of the Historical Society 9. No. 1 (March 2009).

Majewski, John. Modernizing a Slave Economy: The Economic Vision of the Confederate Nation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 2009.

Thornton, J. Mills. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. 1978.

Rothbard, Murray. “America’s Two Just Wars: 1775 and 1861.” in The Costs of War: America’s Pyrric Victories, ed. John V. Denson. New Brunswick, NJ.: Transaction, 1997.

McKitrick, Eric, ed. Slavery Defended: The Views of the Old South. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. 1963.

Merk, Frederick, Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History: A Reinterpretation. New York: Knopf, 1963.

Niven, John. John C. Calhoun and the Price of Union: A Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

Pollard, Edward. The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates. New York: E. B. Treat & Co. Publishers, 1866.

Woodward, C. Vann. “Introduction,” in George Fitzhugh, Cannibals All! or Slaves Without Masters. Baltimore, 1959.