Trump, the Accidental President

Donald Trump is a symptom and not the cause of the decline of the Republican Party.

Trump’s victory in November 2016 is the least surprising thing about his candidacy. While it shocked the punditocracy populating the vast wasteland that is cable television news, the results matched scholarly expectations. Political scientists have created dozens of models for predicting outcomes in presidential elections, some of which were uncannily correct predicting the final vote tally in 2016.

One common theme in these models is that they emphasize structural factors over retail politics, ignoring the personalities of the candidates no matter how odious or charismatic. Instead, they look at basic economic indicators and prior political control of the government. In short, voters like to change which party controls the White House periodically and they reward (or punish) the current occupant’s party for the state of the economy.

In 2016, the fact that there had been a two-term Democratic President whose administration spanned a relatively slow economic recovery meant that the election was expected to favor the Republican nominee regardless of who was selected. The GOP could have nominated an orangutan and been favored by the forecast models. Indeed, despite the best efforts of the actual orange-headed nominee to gift the election to his opponent with a stream of ill-considered remarks and leaked scandals, Donald Trump could not overcome the fundamentals that weighed in his favor.

Four-Dimensional Chess

This did not stop pundits from uttering such effluviant as claiming that Trump’s victory was proof of his unique genius such that he was playing “four-dimensional chess” while everyone else kidded around at checkers. The far more accurate, albeit mundane, explanation is that Trump won because he was the Republican nominee in an election cycle that favored Republicans. But that doesn’t explain his victory in the Republican primaries for which there simply are not the same kinds of predictive forecast models. Perhaps Trump’s nomination, even if not his election, was the result of his native political ability?

This was not the case. Trump’s success in the hunt for the Republican nomination was a product of old collective action problems reintroduced into the American party system. See part one of this series for a detailed explanation of how collective action problems bedeviled party politics in the 19th century and how parties evolved to overcome them. Briefly, when party elites lose control of the nomination process, it leads to swollen fields of candidates, a longer debate schedule, and a higher likelihood of an unrepresentative candidate winning the nomination. This has been the story of the Republican Party: it has ceased to function as a modern party, a devolution that culminated in the nomination of Donald Trump in 2016. Trump is a symptom of the decline of the Republican Party, not its cause.

The Cable Newsification of the GOP

The proximate cause for the decline of the Republican Party is the rise of Fox News. Access to the debate stage and donor lists have been the key tools for party control of the nomination process since the 1970s. By cutting off marginal candidates from the debate stage and funneling large dollar donors to the favored, party elites could keep the field of candidates small, the primary season short, and ensure the nomination of a candidate that would be broadly palatable to independent voters in the general election. Fox News landed like a bombshell in the middle of that system.

By the early 2000s, Fox News had grown into a major media institution, one that enjoyed more influence with rank-and-file Republican voters than the party apparatus itself. At first, this power was used to bolster Republican interests and candidates, especially during the George W. Bush administration. However, the interests of the news network and those of the Republican Party were never perfectly aligned, especially as Fox News cemented itself as the predominant source of news for older Republican voters.

Media outlets have a natural preference for controversy, hyperbole, and outrage because they generate consumer engagement. Modern political parties, on the other hand, seek stability and unity. These divergent interests come in conflict during the primary process. Party leadership prefers a short, fuss-free process that ends in the nomination of a safe, broadly palatable candidate. Media outlets want a long, fireworks-filled process that ends in the nomination of an outrageous candidate because it’s good for ratings. As CBS President Leslie Moonves said of the feisty, bloated Republican primaries in February 2016, “It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.” But as good as it may have been for CBS’s bottom line, CBS did not have anywhere near as much influence within the Republican Party as Fox News. And what was good for Fox News may not have been good either for America or for the Republican Party.

Too Much of a Good Thing

The most significant test of which institution—cable channel or political party—has gained more effective control of the Republican nomination process is looking at the growing number of primary debates and forums. Before Fox News, there would only be a small number of party-sanctioned primary debates, limited so as to prevent the candidates from beating up on the eventual nominee. But now, Fox News can hold an unsanctioned debate and expect most of the candidates to show up.

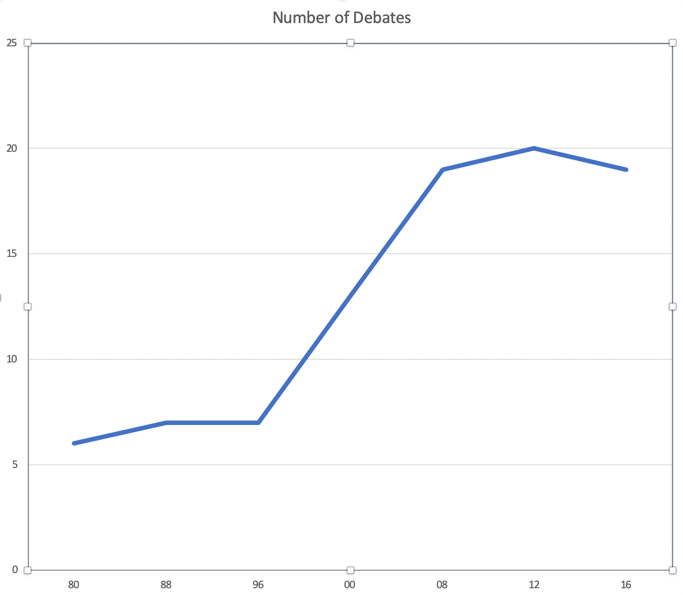

This reflects a long-term expansion in the number of debates in each contested election cycle. As shown below, the number has gone from six or seven primary debates per cycle in the 1980s and early 1990s to nineteen or twenty by the 2010s. It is no accident that the major uptick matches almost exactly the trajectory of Fox News, which covered its first full presidential election season in 2000.

Three times more debates means three times more opportunities for the other candidates to gang up on the eventual nominee, also generating more internal ill will among voters who preferred one of the alternatives. After a record-setting twenty primary debates in 2012, the Republican National Committee finally realized this was a problem and tried to limit the number. Technically they succeeded; there was one fewer debate in 2016 compared to four years before. But given that the party had sanctioned only nine debates and still ended up with nineteen in total, it was another reminder of party weakness. If Fox News or another new conservative media outlet held a debate, there’s not much that the Republican Party leadership could do to stop candidates from showing up.

That is because candidates are no longer as dependent on the Republican Party for access to campaign cash. Back in the days of the party-maintained donor list, only party-approved candidates could get access to the high-dollar donors with whom the party had cultivated relationships. But the party donor list only works as long as the party is the key intermediary between candidates and donors. Fox News and the proliferating number of debates made it easier for candidates to appeal directly to the donor class and to prove their viability—and the potential payoff of an investment in their candidacy—through their debate performances. As a result, individual candidates have been able to build donor lists that effectively compete with those of the party itself, like Ben Carson, who could have made millions from renting his list to other candidates after he dropped out of the primaries in 2016. Furthermore, Fox News provides an additional, sympathetic national platform for candidates willing to call into various infotainment shows in what amounts to a source of free campaign advertising.

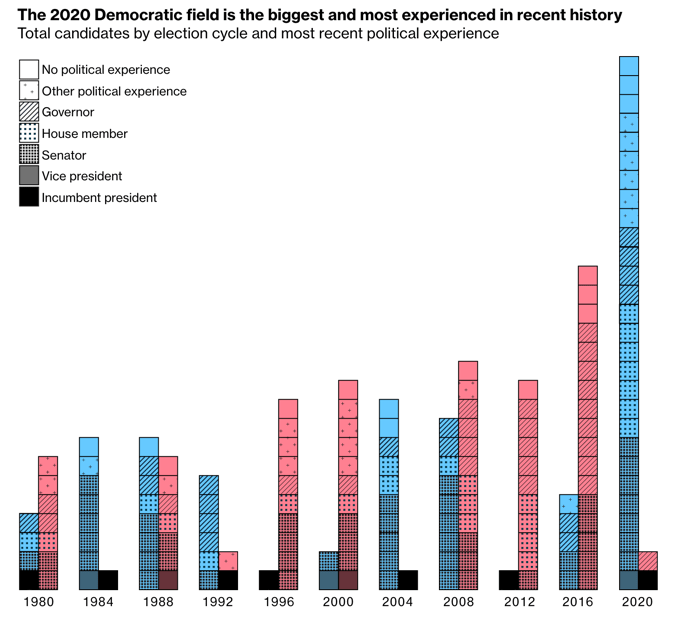

As both main tools of party control have eroded, the number of candidates entering the nomination contest has ballooned, as you can see in the below graphic (from Bloomberg’s Lauren Leatherby & Paul Murray). Instead of seven or so major candidates contesting an open election in the 1980s, the number more than doubled to seventeen Republicans in 2016 and an astonishing twenty-eight Democrats in 2020.

Mention the swelling number of candidates to a partly loyalist and the odds are you’ll hear some variation of how the quantity is a sign of party strength, that it's a good thing the party has so many serious, qualified options. In reality, it’s exactly the opposite, a sign of party weakness; the leadership has been unable to prevent candidates from clogging up the nomination process.

If You Say “Collective Action Problem” Into a Mirror Three Times…

The inability of the GOP to streamline the candidate field is the key sign that the party has ceased to function as a modern party; it no longer optimizes for the general election by controlling the nomination process. As a consequence, in 2016 the GOP was confronted by the kinds of collective action problems that had once bedeviled party politics in the 1820s, as discussed in the first part of this series. For those who haven’t read that essay, a collective action problem arises when individual incentives are misaligned with shared group goals. In primary politics, that means an excessive number of candidates can crowd the field and prevent any single candidate from quickly winning the nomination, unifying the party behind them, and having the best possible shot at winning the general election.

When the field becomes particularly large, it changes how candidates behave. In a small field, candidates quickly take control of one of the ideological “lanes” that represents the aspirations of a particular faction within the party. Those factional standard bearers then fight against one another to see whose faction has the most influence. But when the field is large, the support of any given lane is split between multiple candidates, who then spend more time and resources attacking one another than they would otherwise have to. It is a mini-collective action problem nestled within the party’s broader collective action crisis, a Russian nesting doll of collective action problems.

In 2016 the GOP field was divided between several lanes—between three and five depending on who you asked—including the New Christian Right and moderates. Most of the candidates fit into at least one of those lanes, though all of the candidates, of course, tried to court voters from across the spectrum.

If you were, for example, a religiously-motivated voter in the Republican primaries you tended to support either Ted Cruz, Rick Santorum, Ben Carson, or Mike Huckabee. However, you were significantly less likely to support a twice-divorced, foul-mouthed businessman named Donald Trump. Self-identified evangelicals composed roughly half of the Republican base, meaning that whoever secured that lane, so long as they did it with sufficient rapidity, would have had pole position on the nomination. But the lane was clogged with four major candidates until well into the primary process. Eventually, New Christian Right support consolidated behind Ted Cruz but not until after the vitally important Super Tuesday primaries in early March.

Likewise, the establishment or moderate lane was crowded until quite late in the primary process. By the start of voting, the lane had five major contestants: Carly Fiorina, Chris Christie, Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, John Kasich. But it was the last lane to consolidate, with Marco Rubio and John Kasich splitting moderate support until mid-March.

Why Fight Over the Stairs When You Have an Escalator?

The beneficiary of all this squabbling over control of the lanes was the one candidate who had the least established support in the Republican Party. When Donald Trump first descended his golden escalator to announce his candidacy, his prospects of securing the nomination looked dim. He underperformed with religious voters, was loathed by suburban moderates, and was too liberal on a range of issues for many ideological conservatives. Worse yet, he was widely considered a joke, someone who was just in the race to raise his public profile in time for a new reality tv contract.

Trump’s initial base of support came from the smallest internal faction, the populists, who rejected the party consensus on trade, foreign policy, and economic laissez-faire. They had long had a presence within Republican Party politics, even earning fifteen minutes of fame back when Patrick Buchanan ran for the Republican nomination in the 1990s. However, they mostly acted as marginal irritants.

But what they lacked in raw numbers, the populists made up for with the intensity of their support. Trump’s base was small but quickly became dedicated to him personally. He consolidated the populist lane months before the other lanes had shaken out, allowing him to pick away at the other candidates while they mostly fought with one another. Indeed, when Trump came in second in the Iowa caucuses to Ted Cruz, headlines dismissively declared, “Donald Trump Bubble Burst by Ted Cruz” and “Donald Trump Admits He Lost Iowa Because He has No Idea How to Run a Campaign.” The GOP’s main concern throughout the early stages of the primaries was not that Trump might have a prayer of winning the Republican nomination, but that he would defect from the party and run a third-party campaign in the general election. (This is the one kind of collective action problem that even the most uninformed pundits can understand.) Party control of the nomination process had fallen so far from the days of Martin Van Buren that the best the leadership could do was to ask for a meaningless display of loyalty to the party, a literal showing of hands.

Yet by the time the other lanes had consolidated behind a single candidate, Trump was the frontrunner. This is exactly what you would expect as the outcome from a collective action problem; candidates with the broadest possible appeal, who would otherwise be favored, knock one another out of contention, all to the benefit of a more radical alternative with a unified base of support. Trump might’ve had the smallest initial base of support, but, since it was unified behind him, his support only had to be larger than the one-third or one-fourth share gained by his rivals from one of the divided larger factions.

Even so, it is worth remembering that as long as the nomination was competitive, Trump never managed to win more than a mere plurality of any state’s vote. He secured most of his convention delegates in primaries that he won with around a third of the vote, like South Carolina where his 32.5% of the popular vote netted him a full 50 delegates while the other candidates received none. In fact, Trump’s combined vote total from all primary contests—including those that happened after he was the sole candidate—added up to just 44.9%. A landslide majority of the Republican rank-and-file would have preferred another nominee. How could such a widely unpopular candidate secure the nomination with so slim a base of support?

Pity Poor Priebus

It was partly because of ill-advised voting reforms enacted by party leadership a few years prior. In 2012, the favored candidate and eventual nominee Mitt Romney had faced a long, bruising fight against culture warrior Rick Santorum. And even once Santorum finally bowed out, an outsider candidate with a small but energized base of support—in this case the libertarian Ron Paul—took advantage of the decline of party discipline to seriously contest several primaries, thus preventing Romney from immediately pivoting to his general election campaign.

Both the 2012 slog as well as the 2016 surprise were products of party reforms in 2011 that further destabilized the nomination process. The GOP was facing what amounted to an existential crisis, which demanded a leader with a long-term vision, historical awareness, and a willingness to take decisive action. What they had instead was Reince Priebus, the Chairman of the Republican National Committee.

Priebus’s grand plan was to discourage states that fell early on the primary calendar from having winner-take-all primaries, in which all the delegates went to whomever won the most votes even if it was only a plurality. Winner-take-all votes accelerate the nomination process, allowing a candidate to amass an insuperable lead in delegates early on and forcing second-tier candidates to drop out quickly.

By contrast, primaries that award delegates proportionally peg a number of delegates to every few percentage points that a candidate wins, meaning that half a dozen candidates could come out of a proportional primary with at least one delegate. A proportional vote keeps second-tier candidates viable for longer, discouraging them from dropping out of the race as early. Even a few delegates could be flipped into a staff or cabinet position, so why not stay in the race as long as possible? But if you want a shorter, less contested nomination, you should have more winner-take-all elections and hold them as early as possible. Instead, the party did exactly the opposite, pushing the winner-take-all contests until later in the calendar, slowing down the nomination, and voluntarily giving up party control of the process.

Furthermore, Priebus failed to understand that a collective action problem could boost the election chances of otherwise marginal or radical candidates, especially during a longer nomination process. He simply could not imagine that someone like Donald Trump—who had little institutional support, low popularity ratings, and no political experience—might benefit from changes that he had enacted in order to help the likes of Mitt Romney or another party-favored nominee.

Who Are You Calling an Accidental President??

We have arrived at the fundamental irony of the 2016 election. Trump is an accidental President. The reasons that he won had little to do with his native genius, his campaign’s use of Facebook ads, Russian bot campaigns, or even the failures of his opponents. While those explanations might have some value at the retail margins--and margins do matter when the election hinges on 80,000 votes in three states--Trump’s victory was primarily a product of deeper structural phenomena.

First, Trump benefited from the decline of the GOP as a modern party system. While Fox News was relatively slow to jump on the Trump bandwagon, Trump used his personal connections to prominent Fox hosts and primetime shows to bolster his brand with Republican voters long before he announced his candidacy. His crude antics contributed to making the interminable Republican primary debates must-watch events covered by all the major networks. Trump built his initial base of support on cable television, far outside the control of party leadership, something which would have been nearly impossible prior to the rise of Fox News.

Second, Trump benefited from primary calendar changes enacted years before his candidacy. The resulting protracted knife-fight of a nomination process aided a candidate who had sharpened his skills in the only arena more brutal than politics: reality television.

Finally, Trump benefited from the general political landscape in 2016, running as he did to succeed a two--term Democratic President during a slow economic recovery. He was in the right place at the right time to win the Presidency, as much an accident of history as John Tyler succeeding William Henry Harrison after Harrison died of typhoid a month after his inauguration. Of course, an accidental President has just as much executive power to abuse as any other. Trump’s victory on November 8 might have meant less than most folks thought, but it has meant even more than many expected in the three and a half years since.

Trump’s victory has masked the breakdown of the Republican Party as a modern party system. And it is possible that its failure might continue to be masked in the immediate future despite Trump’s unique unpopularity and the coming demographic crisis facing the aging, white voters who form the core of the party base. That is because the Democratic Party, while somewhat better insulated from that decline over the past decade, is now also being confronted by collective action problems. As a result, Democrats may not be able to take full advantage of a once-in-a-generation opportunity to dominate electoral politics that hasn’t been seen since the New Deal era.

Part three of this series on the Democratic Party’s collective action crisis coming soon.