Looking Back to Look Forward: Blacks, Liberty, and the State

It is not enough to be passively “not racist.” We must be actively anti-racism.

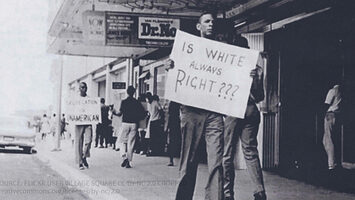

Libertarians tend to think of freedom as either a means to an end of maximum utility—e.g., free markets produce the most wealth—or, in a more philosophical sense, in opposition to arbitrary authority—e.g., “Who are you to tell me what to do?” Both views fuel good arguments for less government and more personal autonomy. Yet neither separately, nor both taken together, address the impediments to freedom that have plagued the United States since its founding. Many of the oppressions America has foisted upon its citizens, particularly its black citizens, indeed came from government actors and agents. But a large number of offenses, from petty indignities to incidents of unspeakable violence, have been perpetrated by private individuals, or by government with full approval of its white citizens. I would venture that many, if not most libertarians—like the general American public—haven’t come to terms with the widespread, systemic subversion of markets and democracy American racism wreaked on its most marginalized citizens. Consequently, libertarians have concentrated rather myopically on government reform as the sole function of libertarian social critique without taking full reckoning of what markets have failed to correct throughout American history.

Take, for example, the common libertarian/conservative trope: “We believe in equal opportunity, not equal outcomes.” Most people, outside of the few and most ardent socialists, should believe that is a fair statement. But to say such a thing as a general defense of the status quo assumes that the current American system offers roughly equal opportunity just because Jim Crow is dead. Yet, that cannot possibly be true.

Think of the phrase “Don’t go there, it’s a bad neighborhood.” Now, sometimes that neighborhood is just a little run down, doesn’t have the best houses, doesn’t have the best shopping nearby, or feeds a mediocre school. But, more often, that neighborhood is very poor, lacks decent public infrastructure, suffers from high unemployment, has the worst schools, and is prone to gang or other violence. And, in many cities—in both North and South—that neighborhood is almost entirely populated by minorities.

There are only two conclusions possible when facing the very real prospect that thousands or millions of Americans live in areas you warn your friends not to go, even by accident: Either everyone in those areas is a criminal, or is content to live among and be victimized by criminals; or there is some number of people, and probably a large one, trapped in living conditions that cannot help but greatly inhibit their opportunities for success and advancement. As Ta-Nehisi Coates lays out in the latest issue of the Atlantic , that those neighborhoods are racially segregated is no accident. Jim Crow’s death is worth celebrating but hardly sufficient for establishing equal opportunity in any meaningful sense, especially when our society still effectively traps people in these conditions by both law and custom, based in no small part on their race.

So what is a libertarian to do about all this?

As I mentioned in my previous essay, libertarians must recognize that racism still plays a practical and tangible role in the lives of American blacks. So long as libertarians brush racism aside as incidental or irrelevant to public policy, people who see and feel its effects in their neighborhoods, in their schools, and in their interactions with police, are unlikely to take what libertarians say seriously. Disparate treatment in education, criminal justice, and the economy are facts of life for many black Americans, and libertarians should take an active role in combating it, both through policy suggestions and in our personal lives. Part of this requires a deeper understanding of American history, and specifically the history of American racism.

Racism has been part and parcel of America since its inception, often to the extent that racism not only trumped common decency and the Rule of Law, but economic self-interest.

On some basic level, representative government reflects the will of the people it serves—that is, those to whom government actors feel most accountable. Historically speaking, within the United States, such a government and a coalition of individuals and institutions—bankers, shopkeepers, restaurateurs, police officers, teachers, judges, landlords, election officials, bartenders, homeowners, receptionists, doctors, and other white citizens—exerted power that threatened to disrupt or upend the lives of black individuals at whim over many years. This white supremacy was true throughout most of the United States, with varying degrees of brutality and certitude. The dominant libertarian assumption that rational economic self-interest would trump racism if government just got out of the way fails to reckon with more than 200 years of evidence to the contrary.

Consequently, the strident libertarian argument against positive law and government writ large flies directly in the face of the historical black experience. The federal government protected the rights of freedmen and established schools during Reconstruction, only to abandon blacks to Southern white terrorism in the name of States’ Rights. Positive law destroyed Jim Crow, breaking up both formal and informal segregation in accommodations not just in the South where it was law, but throughout other parts of the country where it was standard practice within a supposedly free market. The federal government took an active role in criminal justice because local police often did not investigate anti-black terrorism and murders—or, if they did, sometimes testified in the murderers’ defense. And today, governments offer jobs with security and benefits in a job market that still disfavors blacks. This is not to say that blacks are particular fans of Big Government, but all of these government actions addressed problems in private society—ranging from indifference to murderous hostility—that should test anyone’s faith in an unfettered free market. This does not mean that libertarians should embrace positive law going forward, but simply to recognize Madison’s wisdom that “if men were angels, no government would be necessary.”

To wit, while libertarian finger-pointing at New Dealers and early Progressives as racists whose policies excluded or punished black people is based in truth, it is not entirely convincing 70-100 years hence. Whatever one can say about their political preferences, American Progressives have been consciously and conspicuously inclusive of blacks and other marginalized people in the recent past—to their great credit. To equate the Woodrow Wilson Progressives and their Southern Democrat allies with the multiracial, multiethnic coalition that elected Barack Obama is simply unreasonable. Libertarians should challenge the economic wisdom of longstanding Progressive policies, but take away their social programs and you still have a United States fully inhospitable to equal rights for blacks in the early 20th century—for which there was no evident or forthcoming free market solution. (This I note with a touch of irony, given that there is a prevalent libertarian assumption that the dearth of black libertarians is traceable to black ignorance of the benefits of free markets, perhaps enabled by poor public schools. Yet one may argue that libertarians are largely ignorant of how exclusionary American markets were when its moneyed participants were left to their own devices.)

The policies and practices of even well-meaning people put into a system that has traditionally abused minorities is likely to continue to do so, even with new inputs. Systems that operate under choices made by people with biases can still result in outcomes detrimental to a race or group, thus effectively punishing blacks and other people outside of power. This is why focusing on a single policy program, like the Drug War, in some ways misses the forest for the trees when it comes to how blacks and the criminal justice system have interacted over time.

Certainly, the Drug War has been the largest driver of the disproportionate black and Hispanic prison populations in recent years, both through the incarceration of non-violent offenders and prosecuting those people involved in the violence associated with prohibition regimes. But the tensions between blacks and the American justice system did not start with Nixon’s War on Drugs in 1971.

Before Emancipation, law enforcement hunted down fugitive slaves who fled to the North. After Reconstruction, local law enforcement stripped the recently won civil rights of blacks, including the right to peaceably assemble, the ability testify against white people, and equal protection of the laws. Some offenders, picked up for charges like vagrancy—that is, being black and without a job—were sold back into civil slavery to corporations the profit of local sheriffs’ offices and judges under the “convict lease” system—not unlike slave leasing in the antebellum South. Years later, police officers were among the civil servants who sicced dogs, swung batons, and unleashed fire hoses on protesters in the 1960s. Special Weapons [A]nd Tactics teams, or SWAT, were established in the 1970s to help quell white fear of racial unrest and militants such as the Black Panthers. The 1980s saw drug enforcement ramp up, turning American inner cities into war zones. And perhaps most famously, in the 1990s, a home video showed several Los Angeles police officers beating black motorist Rodney King within an inch of his life. Today, SWAT-style raids as standard operating procedure, anecdotes of “driving while black,” and the documented abuse of Stop-and-Frisk tactics in New York City evince the continued tension between law enforcement and black Americans. If the Drug War were to end tomorrow, any belief that the tensions between blacks and the police would stop must be based on entirely ahistorical assumptions.

Most criminal laws since Reconstruction are facially “colorblind,” but enforcement clearly is not and has never been. Context matters, and in the American context, race matters. So when we, as libertarians, talk about what we can do to change people’s lives for the better, we have to look at exactly what they’re facing and what practical solutions look like. For black Americans, many of those problems have been around for a very long time, in one form or another, and they are directly tied to race.

So, yes, libertarians should continue to argue vehemently against the Drug War, for school choice, and in support of other policies that have been shown to help all people. But it is simply not enough to believe that, given free choices, citizens will make decisions that maximize their own benefit, ultimately to the benefit of all people. The United States’ long history with both public and private discrimination is a testament to the power of racial prejudice and its power to overcome rational self-interest. And given the numerous statistics now available—from unemployment disparities to tracking hiring practices to police harassment—it is clear that lingering prejudice contributes to unequal opportunities for American blacks, on top of the myriad obstacles they may face in their neighborhoods and schools.

Libertarians need to actively combat racial prejudice instead of relying on assumptions that the market will work it all out on its own. If libertarians are going to maintain that government answers to racism are usually inappropriate, then libertarians must be among those leading the private, society-driven remedies to injustice. It is not enough to be passively ‘not racist’—libertarians must be actively anti-racism. To do anything else is to accept the status quo and hide behind the logic of markets, despite the deeply seated, inherent illogic of racism.

This means, inter alia, discussing racial impacts of substandard schools (perhaps allaying fears that school choice will lead to more segregation academies), the pernicious effects of antagonistic policing, and explaining whose jobs will likely be lost due to a minimum wage hike. It means trying to remedy the longstanding disconnect between those who push for punitive laws and those who suffer under them. It means supporting community programs to encourage entrepreneurship and funding scholarships for aspiring business leaders. It means talking to black people and audiences like intelligent individuals whose life and family histories may temper enthusiasm for free markets, and not a mass of people too ignorant or dependent to believe in a theoretical version of freedom unknown to them. It means vocally and unequivocally distancing ourselves from people with longstanding racial baggage, be it Confederacy revisionism or career obsessions with black pathology. Then, maybe, libertarians’ “It’s not us, it’s you” message of liberty would turn into something different: a message better received by people with memories of how duplicitously the words “freedom” and “liberty” have been used in this country.