LITERALLY HITLER

Nazi comparisons serve the rhetorical purpose of designating one’s political opponents as acceptable targets for extreme, even violent, actions.

Perhaps it’s an occupational hazard of writing novels about Nazis that you’ll be accused of being one. Last month, my first novel, The Hand that Signed the Paper , was reissued with some fanfare. Australia’s national daily published the new introduction I wrote for it [paywalled].

Since then, the inhabitants of my Facebook in-tray have been keen to tell me I’m “LITERALLY HITLER.” Many of them helpfully included a link to my piece, as though I didn’t know or recall what I’d written.

This, I’ve discovered, is a deeply millennial moniker, with its origins in SJW tumblr. Twitter – home to fewer millennials – prefers “Nazi apologist.” One particularly fixated tweep forgot David Cameron’s First Law of Twitter (“too many tweets make a twat”) and spent the best part of half a day tweeting about Nazi apologism not only at me but at the Telegraph’s opinion editor as well.

Since we were clearly ignoring him, I started to wonder why he bothered. I mean, people have jobs and lives and surely sitting abusing people on Twitter all day is slightly less interesting than navel-fluff collecting.

Given Trump, Brexit, and Marine Le Pen, Hitler comparisons are also everywhere in the news; it’s sometimes as though the world’s media has been taken over by extras from The Producers. Nazism is no longer reserved for errant novelists and heavy metal bands rather too fond of makeup.

The problem, of course, is that Hitler was a singular case, the “5 sigma of nutters” as my high school maths teacher once put it. This makes the comparisons little short of bonkers.

The mixed horror and fascination Nazism also elicits has weird effects. When I put out a call to friends to share their thoughts on Hitler analogies, one of Sky News’s anchors (Sky is the UK and Australian equivalent of Fox News) told me how her 12-year-old son and all his school friends are “unnaturally obsessed with Hitler” and “compare any world leader of the moment to him,” all while ignoring everyone else. There doesn’t seem to be a place in their affections for Julius Caesar or Genghis Khan. Like me, she’d like to know why.

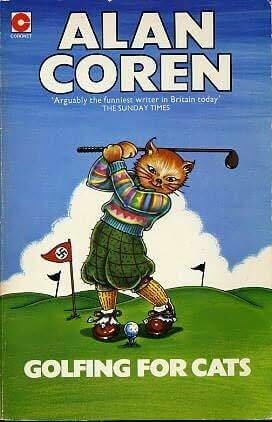

There’s also marketing research showing books about Hitler, golf, and cats are wildly popular (why those three?). This suggests an author who combined them in just the right way would probably land on Free Parking in Monopoly. In the 70s, British comedian Alan Coren (successfully) put this research to the test with his book Golfing for Cats . Its cover featured a ginger tom in plus fours driving towards a swastika pin flag.

And, of course, there’s the Hitler, whoops, History Channel.

Marine Le Pen is most commonly compared to Hitler, in part because her Front National has genuine historical links to the collaborationist Vichy regime. Yet, she is probably better characterized as a garden-variety authoritarian populist than an out-and-out Nazi. She was willing to boot her own father out of the FN to sever the Vichy association. The simple fact of her sex would also be enough to rule her off-limits to any genuine Nazi.

The same goes for Donald Trump, but with even greater force. There are presidents famous enough to have their faces on banknotes and stamps (Andrew Jackson, natch) who held policy positions remarkably similar to Trump’s. Those views and ideas are an important – if neglected – part of American intellectual history.

Quite apart from a place in their national political traditions, neither Trump nor Le Pen command private, uniformed paramilitary forces capable of holding the State to ransom, the signature characteristic of both Nazism and Mussolini’s fascism.

So why do people insist on comparing their opponents to Hitler? One suggestion I’ve had is “because it feels so satisfying.” However, masturbation is also satisfying and we’ve managed to keep that out of the nation’s newspapers for the most part. Wheeling out the ultimate Big Bad is a Big Thing, a phenomenon deserving of closer examination.

To my mind, part of the problem is that political polarisation in liberal democracies means while we no longer agree on what is good and right, we do agree on what is bad or evil. Hitler is definitely bad and evil, ergo calling a political opponent a Nazi or comparing a politician to Hitler is a shorthand way of consigning him or her to a sort of moral outer darkness. You’d never apply the Hitler epithet to someone with whom you disagreed, but otherwise thought was basically sound. Cato’s own Jason Kuznicki – in a splendid piece called, entirely appropriately, “In Search of a post-Godwin Politics” – enumerates:

Consider the myths that we all cherish: the president of the wrong party is dangerously incompetent. He fawns unacceptably in front of certain foreign leaders. He shows contempt for tradition and for the unwritten rules of the office. He is himself under the sway of foreign ideas, foreign advisors, and foreign money. Long-term, he will end American democracy. He will replace it with authoritarianism, a brutal and nefarious plan that he has masterminded for years and years. He may just be our last president.

And there will be camps. Oh yes, there will be camps.

There are always camps. We do not disagree on this fact. We disagree only on just whose face will appear on the jumbotron over the sign reading Arbeit Macht Frei. Camps are a permanent fixture of the political imagination, if not of the actual landscape. One hardly dares to predict otherwise; it seems rude to deny the general opinion about what we’re in for. Which is bog standard Adolf Hitler.

Kuznicki rightly observes that Hitler comparisons are a game all sides of politics can play, depending, of course, on who currently occupies the Oval Office. His account of similar hyperventilating about Barack Obama from a few years ago is salutary.

Which leads us back to the rhetorical work Hitler analogies do.

If the modern Anglosphere has a mythology, a “Just So” story, it’s that we deserve to be rich and powerful because we fought the Nazis. They stood for tyranny while we stood for freedom.

As Churchill put it before the Battle of Britain in 1940: “If the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will say, ‘this was their finest hour.’” The Empire didn’t last another 30 years, of course, but that hour is looking finer and finer as each year passes. The Nazi threat was an existential one, and the whole industrial, intellectual, and productive capacity of the Anglosphere was directed to defeating it – by any and all means necessary. Our violence was unquestionably legitimate, but we tend to forget that 80% of Germany was rubble by May 1945. We really did bomb it back to the Stone Age.

This Just So story provides a great peg for one of the oldest and most successful psychological in-group narratives. When someone says “you are literally Hitler,” they’re effectively making a death threat, asserting that any violence against you should be both warlike and extra-judicial, so justified is it morally.

It’s a way of telling you you’re not really part of the demos; that as a moral outsider, your existence is unwelcome.

Reasonably obviously, this is lazy hyperbole. The scale is wrong and instead of intensifying the horror those who throw Nazi accusations about feel, it serves only to make them look ridiculous. It makes rational debate difficult and only encourages hyperventilation about the contemporary populist revolt in liberal democracies. It also impoverishes our political discourse, and no doubt contributes to an environment where the first historical figure to pop into sundry 12-year-olds’ heads is Hitler.

“Godwin’s Law” of the Internet is probabilistic – it states, “as an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Hitler approaches 1.” Perhaps it should be made blunter, to discourage the practice: “the first person to make a Hitler analogy in a debate loses.”

I’d also suggest, rather than Hitler comparisons or attempting to belt opponents over the head with facts and fact-checkers, people interested in political debate ask what it would take for a given individual to change his or her mind. Philosopher Peter Boghossian explains:

This strategy is effective because asking the question, “What evidence would it take to change your mind?” creates openings or spaces in someone’s belief where they challenge themselves to reflect upon whether or not their confidence in a belief is justified. You’re not telling them anything. You’re simply asking questions. And every time you ask it’s another opportunity for people to re-evaluate and revise their beliefs. Every claim can be viewed as such, an opportunity to habituate people to seek disconfirming evidence.

Trump is not Hitler. Le Pen is not Hitler. Julius Caesar and Genghis Khan are both more interesting historical figures than Hitler. Debate about the EU and its role has been part of British politics for decades; Brexit was always possible. Authors who write novels featuring believable and sympathetic Nazi characters are not Nazis. No one is going to any death camps.

Most importantly, your political opponents are not moral dwarfs, to be consigned to outer darkness because they disagree with you.