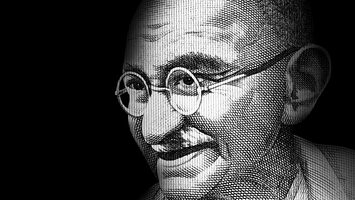

Gandhi: A Champion of Freedom Who Defied Political Labels

Gandhi saw civil resistance as a way to accept suffering and sacrifice in order to make the other side realize the justness of the cause.

Less than six months after India gained Independence from British colonial rule, Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu fanatic on January 30, 1948. The Cold War was looming as a result of constant tension created by countries embracing socialism as an after effect of World War II. Today, the legacy of politicized Hinduism or Hindutva is practiced by India’s governing political party. While those in power have not condoned Gandhi’s murderer, they have continued to eulogize the Hindutva ideology which motivated that crime.

On the one hand, social religious conservatives accuse Gandhi of being a radical seeking to weaken traditional Hindu values. On the other hand, the radical Left, who reject Indian democracy, also condemn Gandhi for his apparent religiosity. Socialists in India and elsewhere have often laid claim on Gandhi’s legacy while ignoring Gandhi’s fundamental critique of the inherent dangers of state power. Liberals are still conflicted between Gandhi’s amazingly progressive social views, and his apparent critique of economics and technology that symbolize modernity and progress.

So, who was Gandhi? And how does he fit into political tradition, if at all?

Quest for Gandhi

No one could have predicted that liberalism as an ideology would be marginalised from the political scene not even three decades since its’ highpoint at the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The use of the word liberal in this context refers to its’ classical liberal meaning; to depict the political ideal that calls for greater civil, political and economic freedoms for the individual, and less government control. There is a case to be made that Gandhi was both the last classical liberal and the first libertarian 1 .

Exploring Gandhi requires a firm review of the state of liberalism today. Do liberals today realize who they are claiming when they set Gandhi as a prominent figure of liberal ideology?

Before Gandhi arrived on the Indian political scene during the second decade of the 20th century, the Indian National Congress was primarily an association of enlightened citizens petitioning the colonial British government for various political and economic reforms. Gandhi transformed Congress into a mass movement. A movement of this kind had never occurred in the world before—or since. He engaged with capitalists and peasants, industrialists and workers, the rich and the poor, the socially privileged and the discriminated, the elite and those at the margins of society, in order to build a movement that shook the political and moral foundations of colonial rule.

Non-violent Revolution

Gandhi is easily the greatest mobilizer of people. He will be forever known as the most prominent non-violent revolutionary. While it may seem that his political principles have not found much favour among the dominant ideologies of today, the Gandhian methods of nonviolent mass mobilization persist. He orchestrated boycotts, pickets, and hunger strikes that continue to fascinate the world. The entire political spectrum takes interest in Gandhi’s work because they too would like to mobilize people in this fashion.

An empirical analysis of the efficacy of civil resistance in the 20th century from across the world shows that non-violent methods have been twice as successful in changing authoritarian regimes as violent revolutions 2 . The study questions some of the common perceptions that non-violent struggles succeed only in a liberal democratic polity. It also calls in to question that political struggles ultimately necessitate coercion and violence in some form, implicit or explicit, when all other forms of actions and protests for reforms fail.

Nonviolence is key to appreciating the scope of Gandhi’s political activities. Unlike nonviolence, violence primarily affects common people by replacing those in power and leaving the institutions of injustice and oppression intact. The focus on people rather than on the nature of the institutions, inevitably raises the personal stake, entrenches the divisions, thus intensifying the conflict. This approach of personalizing and escalating conflict, on the one hand institutionalizes violence, and on the other normalizes violence in society.

Gandhi, therefore, sought non-violence, not just as a moral force, but also for it’s strategic and tactical value.

This enabled him to integrate principles and practices of politics in a very creative yet effective ways. He focused on reforming the nature of politics, while looking at those holding power as legitimate political opponents, not enemies, allowing him to cultivate an environment for possible cooperation with the political opponents.

There are countless examples of Gandhi being able to extend an olive branch to those who opposed his viewpoint. For example, General Jan Smuts was the British Administrator who had jailed Gandhi in South Africa. The two confronted each other a number of times. Yet on Gandhi’s 70th birthday, Smuts sent a note returning a pair of leather sandals Gandhi had given him when he was leaving South Africa in 1915. Smuts wrote, “It was my fate to be the antagonist of a man for whom even then I had the highest respect… … In gaol he had prepared for me a very useful pair of sandals which he presented to me when he was set free! I have worn these sandals for many a summer since then, even though I may feel that I am not worthy to stand in the shoes of so great a man! Anyhow it was in that spirit that we fought out our quarrels in South Africa. There was no hatred or personal ill feeling, the spirit of humanity was never absent, and when the fight was over there was the atmosphere in which a decent peace could be concluded.” 3 In the world today, it is difficult to imagine political adversaries with so little rancour.

Satyagraha or Civil Resistance

Gandhi’s first experiment in Satyagraha 4 was in South Africa in 1908, on behalf of the migrant and indentured labourers from India to counter racially discriminatory laws against Asians. Although, greatly influenced by Henry David Thoreau’s more passive and personal “Civil Disobedience” 5 , Gandhi turned it into active and public act of civil resistance.

Satyagraha had its share of critics. Apprehension toward civil resistance as modes of protests beyond institutional and constitutional frameworks was not a new fear. At the dawn of independence, B.R. Ambedkar 6 and others had argued that while civil resistance had a role under colonial rule when people didn’t have a voice, it ought not find any place in independent India with the people electing their representatives in the democratic republic.

Involving more people in political action, however, required better control over the nature of the protests, and the passions of the protesters. The distinctive aspect of Gandhian Satyagraha was the central role of the individuals engaged in political action to suffer and sacrifice, moving towards self-mastery and self-discipline. This was intended to help the volunteers turn the focus inwards, to the moral values underlying the political protests, rather than just the objection of the protest. The staging of the non-violent protests with discipline and dignity rendered the instances of civil resistance into a more persuasive form of direct action, than either physical violence or other kinds of overt coercion and intimidation involved in traditional forms of mass action. 7

Reforming the self was a key component of social and political reforms, because Gandhi saw society as the sum total of individuals. This was important since Gandhi sought to inspire his people into political action. Gandhi wanted aware and informed citizens rather than organizing movements using the masses as props.

Gandhi’s approach to political protests evolved as he experimented with ways of narrower localized issues relevant to relatively small, clearly identified groups of people, as in South Africa 8 and Champaran 9 . These political campaigns prepared Gandhi for his much larger anti-colonial nationalist movement because in that case he needed to engage with almost every section of Indian society. However, irrespective of the scale and scope of political action, Gandhi always sought to highlight the justness of the cause, and strived to convert political opponents for the cause of justice.

Gandhi valued political reconciliation to ensure justice and peace in society and, consequently, he was always willing to negotiate once the principle at stake was recognized.

Some look at public defiance of the law as a recipe for anarchism and breakdown of social and political order. Some point to potential for criminalization by surreptitiously avoiding or breaking the law for personal gain under the cover of civil resistance. Others, including some of his key colleagues in the Congress Party felt exasperated by Gandhi’s willingness to negotiate with his political opponents.

Gandhi was aware of these criticisms. His strenuous rules of Satyagraha were evidence not of disregard for laws but of upholding laws that are ethical and effective. Thus through the rules of Satyagraha, he sought to uphold the institutions of laws that were just. This differentiates Satyagraha from an anarchic disregard of laws or deliberate subversion of laws by criminals. 10 Satyagraha was therefore the means to Swaraj, or self-rule, which was the ultimate goal.

An ideal satyagrahi, Gandhi wrote in his autobiography, is one who “obeys the laws of society intelligently and of his own free will, because he considers it to be his sacred duty to do so. It is only when a person has thus obeyed the laws of society scrupulously that he is in a position to judge which particular laws are good or just and which [are] unjust or iniquitous. Only then does he accrue the right to civil disobedience of certain laws in well-defined circumstances.” 11

Mechanics of Mass Movements

As Gandhi ventured into his first major national campaign in 1920, he claimed not to be a visionary, but a ‘practical idealist’. He wrote, “The religion of non-violence is not meant merely for the rishis 12 and saints. It is meant for the common people as well. Non-violence is the law of our species as violence is the law of the brute. The spirit lies dormant in the brute and he knows no law but that of physical might.” 13

Gandhi drew from the daily experiences of people where the overwhelming majority interacted with each other peacefully, in the belief that their interactions are just and proper. Conflicts were an exception, rather than the norm.

The exemplary behavior by the core volunteers, trained for Satyagraha, led by example, which added a moral halo to the cause, helping to diminish the fear of political power. The satyagrahis inspired many and acted as guides for people to follow. With the decline in fear bolstered by righteousness of the cause, more and more common people came out to claim ownership of the movements locally, thus making the campaigns go ‘viral’.

Increased participation in the campaigns provided opportunities to deepen engagement with the specifics of the particular issues, and enhanced awareness of the fundamental principles at stake.

Gandhi was very aware of the hazards of passions released once a large number of people began to participate in the political campaign. His organizational genius lay in designing constructive programs to channel those passions. His stress on rules such as celibacy, hygiene and food habits, honesty and civility, and adoption of the spinning wheel or the charkha 14 , were all aimed at imparting self-control.

Gandhi’s advocacy for the spinning wheel was one of the ways he sought to inculcate self-discipline, instil a sense of dignity of labour, and inspire personal independence. Through such productive participation, even from the confines of one’s home, people could feel connected with the larger Independence movement against British rule.

In 1930, Gandhi conceived and led the Salt Movement, which, on the face, was a protest against the state monopoly over a commonplace substance. Today, the Salt Movement has become almost the benchmark of mass movements across the world. But at that time, many of Gandhi’s senior colleagues, including Nehru were not able to fully appreciate the significance of such a common ingredient like salt, with the greater cause of national Independence. Yet the spontaneous participation of millions in the campaign to defy the salt law, showed the British that they would not be able to govern India for long without the consent of the governed 15 . Even more importantly, the campaign made the Indians realise that the power of the law depends on their consent as citizens. It completely reversed the conventional relationship between the rulers and the ruled.

The combination of participation, practices, and principles rapidly built a sense of citizenship. No formal education process could have hastened or deepened such feelings of belonging to such large numbers as these mass campaigns did.

Gandhi laid out a strenuous set of rules of engagement for satyagrahis participating in various movements. Hartal, typically a day of stoppage or strike, was a common instrument deployed locally and nationally since the Non-Cooperation Movement in the early 1920s. The day of stoppage was announced well in advance to allow the people to prepare for possible inconveniences, even while the volunteers campaigned among the public to drum up support for the cause. But on the day of action, volunteers were asked not to forcefully stop anyone from going about their work.

Political actions are always pregnant with the possibility of violence. Such restraints on the part of the organizers of the protests significantly helped reduce tension on the actual day of action, thus lowering the potential for provocation and violence.

While the idea of nonviolent protest movements have spread far and wide, the gulf seems to have widened between the way Gandhi sought to leverage civil resistance and many of the later generation leaders of nonviolent movements. The Dalai Lama, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela would be among the leaders who were more attuned to Gandhi’s way of peaceful political action, as a reflection of the moral force, rather than merely the force of numbers. On the other hand recent mass protests, such as the Occupy Movement in 2011-12, or the recent mass protests in Hong Kong in 2019, while largely peaceful, also relied a lot on the strength of numbers to force a sense restraint on the state. This is reflected in the entrenched political positions with neither side willing or able to find a way to negotiate with each other.

Gandhi saw civil resistance as a way to accept suffering and sacrifice in order to make the other side realize the justness of the cause, and potentially ‘converting’ them to the side of justice. Most of Gandhi’s opponents trusted him while disagreeing with him. In today’s politics, trust never gets a seat at the table.

However, the declining credibility of politics and the diminishing trust in the politicians themselves are not an overnight phenomenon. The ball had been rolling for a few centuries, and the current lament regarding extreme polarisation in politics is a culmination of that process. The recent rise of populist leaders from across the political spectrum may seem to confirm political polarisation and divergence of ideologies. At another level, populism is also an illustration of convergence of ideologies, where the primary focus is on capture and use of political power, rather than how that power may be used. They wrap themselves in nationalist garb and proclaim the illegitimacy of political critics and their opponents. This is a manifestation of the inevitable breakdown of trust between political actors and amongst leaders and their followers.

Despite the apparent breakdown of politics at one level, on another level, however, there prevails an uncanny unanimity across the political divide. All sides express complete faith in harnessing the power of the state for their particular political objectives. This means that the purpose of politics shifted from the art of managing political differences, to the practice of capturing power, any which way possible. Then that treasured power is used to hammer any and all opponents into submission or silence.

It is in this context that Gandhi’s practice of non-violence, becomes relevant not just as a matter of principle, but of extreme practical and political significance in the contemporary world. Gandhi’s fundamental critique of the state is premised on the principle of non-violence. It calls for a deeper recognition of the real nature of the state, and therefore requires a constant vigil to restrain the state to a bare minimum. Only when politics begins to move away from the desire to exercise power over others, can practitioners of politics begin to regain the trust they lost. This may make Gandhi’s politics even more relevant globally in the 21st century, beyond his undoubtedly unique contribution to India’s struggle for Independence in the 20th century.

This piece has been significantly updated since its original version in How Liberal is India.

1. Looking at Gandhi primarily as a political leader in the 19th century and 20th century, there may hardly have been anyone like Gandhi, so influential and yet so fundamentally and so consistently cautioning against the ills of an expansive government. Certainly a sharp contrast to the most major political figures of his day, as much as today.

2. Chenoweth and Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. 2008

3. Rt. Hon. Jan C. Smut, “Gandhi’s political method”, published in Mahatma Gandhi: Essays and Reflections on his Life and Work, edited by S. Radhakrishnan, 1939.

4. Satyagraha is a term coined by Gandhi, which literally means the quest for truth or the love of truth. Gandhi translated it to as the “soul-force” or the “truth-force”. Active civil resistance conceived by Gandhi had to be not only non-violent, but required participants to completely eschew hate towards their opponents.

Gandhi showed that this was possible when the participants in the civil disobedience instilled an absolute sense of love for truth. Only then Gandhi argued can the critics and opponents be won over by helping them to grasp the truth, and therefore the justness of the cause. Gandhi didn’t see his political opponents as enemies to be vanquished, but friends to be won over.

5. Henry David Thoreau’s classic essay popularly known as “Civil Disobedience” was first published as “Resistance to Civil Government” in Aesthetic Papers (1849).

6. Dr Bhim Rao Ambedkar, who came from the socially ostracised and economically oppressed lower caste Dalit community, was a member of the Constituent Assembly and the chairman of the committee that drafted the Constitution of India in 1949. He was the first Law Minister in Independent India, 1947-51.

7. Mantena, Karuna (2017). The Theoretical Foundations of Satyagraha,

8. In South Africa, Gandhi organised the various segments of Indian society against racially discriminating laws. These movements culminated in to the first act of Satyagraha on 11 September 1908.

9. In Champaran district in Bihar province in eastern India, in 1971, Gandhi was invited to take up the cause of the farmers who were forced to grow indigo by the British planters. This was Gandhi’s first major political action in India, and attracted national attention, many talented and patriotic young Indians got attracted to Gandhi following this movement.

10. Mantena (2017)

11. Gandhi, M.K. Autobiography, An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth. (1959 edition)

12. A Sanskrit term for enlightened persons who helped compose the Vedas, or Holy men who are completely dedicated to pursue the ultimate truth and eternal knowledge.

13. Young India, 11 August 1920, p.3

14. A charkha is a traditional spinning wheel on which cotton would be spun into thread or yarn. Gandhi adopted the spinning wheel as a symbol of protest against oppressive British laws that deprived India of cotton, and enabled Britain to sell higher value textile in India. It was also Gandhi’s way of inculcating the dignity of labour, in a highly stratified caste ridden society. This was a critical component of preparing the key volunteers who would be at the forefront of many of the civil disobedience campaigns that Gandhi would launch. Spinning was a part of Gandhi’s own daily routine as well.

The spinning wheel was typically operated at home, and provided the input for the textile industry before industrialisation. The spinning wheel is believed to have originated in the Islamic world around 1000 AD, and spread around the world. Variations of the spinning wheel was developed in many different parts of the world.

15. On March 12, 1930, Gandhi began the iconic Salt March with 78 followers, from his camp in Ahmedabad. By the time they reached the sea at Dandi, a small village, on April 6, after walking for 240 miles, the crowd had swelled to tens of thousands. The Salt Movement continued for about eight months, and in that period British arrested around 60,000 to 80,000 people, among them Gandhi and almost all the top leaders of Congress. At least a few million people may have participated either as a part of a coordinated campaign of the Congress workers, or individually, making or selling salt.