Black Women Abolitionists and the Fight for Freedom in the 19th Century

Presley gives a rundown of some of the many black women, both famous and lesser-known, who worked toward the abolition of slavery.

We’ve all heard of Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman. Many other black women made important contributions to the abolitionist movement, too. But the collective efforts of black women had been largely ignored until scholarship in the late 20th century. Though some black women abolitionists came from comfortable middle-class families, many others were working-class women relegated to the poorly paid jobs of laundress and domestic. The Forten family and Sarah Douglass were freeborn, but many others were former slaves. But, for all these women, abolition had a different and more personal meaning than it did for whites. Though black men welcomed them, says historian Shirley Yee, the expectation that they would play subsidiary roles confined to “women’s sphere” was no different than the expectations of white men abolitionists in regard to white women’s participation. Not surprisingly, both the white and the black women saw things differently than the men.

Champions of Justice

Black women were in the forefront of abolitionist lecturing and writing.

In September, 1832, free black domestic Maria W. Stewart (1803-1879) became the first American woman to address a public audience of women and men. She spoke out against slavery, criticizing black men for not standing up and being heard on the subject of rights. Maria wrote both pamphlets and speeches for William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator until she retired in 1833. Another black woman, Mary Prince (1788-c. 1833) wrote a book, The History of Mary Prince: A West Indian Slave, which exposed the horrors of the Caribbean slave trade. She was the first woman to present an anti-slavery petition to Parliament.

Sarah Mapp Douglass (1806-1882) was an abolitionist, writer and educator. The freeborn daughter of Robert and Grace Douglass, a distinguished black abolitionist family in Philadelphia, she joined her mother Grace as a founding member of the bi-racial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFAS) in 1833. Throughout her abolitionist career, Douglass also served as recording secretary, librarian, and manager for the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, contributed to both the Liberator and the Anglo-African Magazine, became a fundraiser for the black press, and gave numerous public lectures. She ran a school for free black children in Philadelphia. “A passionate educator,” she also taught black children and adults in New York. In 1853, she took over the girls’ preparatory department at the Philadelphia Institute for Colored Youth, offering courses in literature, science, and anatomy. Douglass maintained a long and close friendship with prominent white abolitionists Sarah and Angelina Grimké, daughters of South Carolina slaveholders. In her letters to Sarah Grimké, Douglass revealed the pain of encountering race prejudice among fellow Quakers.

Grace Douglass and daughter Sarah, along with white feminist Lucretia Mott, were often able to persuade white organizations to include a black abolitionist perspective. Thus, as historian Janice Sumler-Lewis points out, they became not just well-meaning ladies but an “aggressive, persistent force for change in the Philadelphia area.”

The Forten women (mother Charlotte; daughters Sarah, Margaretta, and Harriet; granddaughter Charlotte L.) were major driving forces in the abolitionist movement. Through three generations, the Fortens remained active members of and financial contributors to the abolitionist movement. Not only did they organize informational fairs and run petition drives, they published and lectured as well as assisting runaway slaves. They were so admired by Garrison and other abolitionists that Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier lauded them in his poem “To the Daughters of James Forten.” Sarah Forten (1814-1893), a regular contributor to The Liberator, recruited her mother, Charlotte, and her two sisters, Margaretta and Harriet to join in founding PFAS. Sarah Forten, along with Sarah Douglass, were among the most articulate and persistent voices in the antislavery movement. Sarah Forten served three consecutive terms on the Board of Directors of PFAS. Charlotte L. Forten Grimke (1837-1914), granddaughter of Charlotte, contributed to The Liberator and was a poet and educator.

Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman: Icons of the Movement

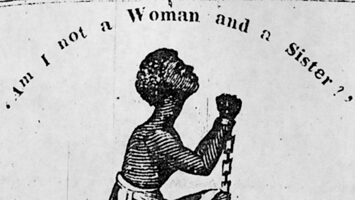

Sojourner Truth (c. 1791-1883) was born as Isabella, a slave of Dutch-speaking settlers in New York. As a result of her experiences of injustice and inequality, as well as contact with feminists and abolitionists, she lectured extensively on antislavery and women’s rights, becoming one of the most well-known and respected heroes of the abolitionist movement. By 1846 Sojourner Truth had joined the antislavery circuit, traveling with Abby Kelly Foster, Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and British member of Parliament George Thompson. An electrifying public orator, she soon became one of the most popular speakers for the abolitionist cause. Her fame was heightened by the publication of her Narrative in 1850, related and transcribed by Olive Gilbert. With proceeds from its sale she purchased a Northampton home. In 1851, speaking before a National Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio, Sojourner Truth defended the physical and spiritual strength of women, in her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. In 1853 Sojourner’s antislavery, spiritualist, and temperance advocacy took her to the Midwest, where she settled among spiritualists in Harmonia, Michigan.

“I cannot read a book,” said Sojourner Truth, “but I can read the people.” She dissected political and social issues through parables of everyday life. The Constitution, silent on black rights, had a “little weevil in it.” She was known for her captivating one-line retorts. An Indiana audience threatened to torch the building if she spoke. Sojourner Truth replied, “Then I will speak to the ashes.” In the late 1840s, grounded in faith that God and moral suasion would eradicate bondage, she challenged her despairing friend Douglass with “Frederick, is God dead?” In 1858, when a group of men questioned her gender, claiming she wasn’t properly feminine in her demeanor, Sojourner Truth, a bold early feminist, exposed her bosom to the entire assembly, proclaiming that shame was not hers but theirs.

Every American school child has heard of Harriet Tubman (1820-1913), undoubtedly the best known of all the female abolitionists. Called “General Tubman” and the “Moses of her people,” she has taken on a larger-than-life persona. Frederick Douglass said of Tubman: “The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witness of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism.” In her own day she was called “the most remarkable woman of her age for her courage and success in guiding fugitive slaves out of slave territory in the 1850s and for her Union service behind Confederate lines,” reports one of her biographers, Jean Humez.

Escaping from slavery in 1849, Tubman quickly became involved with abolitionism. Though she was not a lecturer, partly because of a speech impediment from an injury sustained while a slave, she was a tireless activist, making alliances with women’s rights groups as well as abolitionist groups. Respected by both blacks and whites, she worked with abolitionists as part of the Underground Railway, and probably even brought fugitives to the home of Frederick Douglass.

Though she did not start the Underground Railway, Tubman is the name most associated with it. Recent scholarship suggests that the number of slaves she spirited away from the South may be less than once thought, but this in no way diminishes her courage and cleverness. The estimates range from as few as 10 trips up to about 19, with the number rescued ranging from 57 to 200. But nonetheless, she risked her life to rescue many slaves, both relatives and other men and women, leading them through dangerous and difficult Southern terrain to freedom in the North and in Canada. Her successes were due to both clever disguises and unwavering courage. Fierce in her determination, she would not tolerate slaves who were faint-hearted along the way, even threatening some with guns. Babies were given paregoric (a kind of sedative) to keep them from crying. She became so notorious for her exploits that that a large reward of $12,000 was offered by the South for her capture.

Other Prominent Black Women Activists

There were many more black women abolitionist activists than will fit in this column. But there are some who should be mentioned for their outstanding courage and ability.

Elizabeth Freeman (1742-1829) was born into slavery in Claverack, New York in 1742. Upon suffering physical abuse from her master’s wife, Freeman escaped her home and refused to return. She found a sympathetic ear with attorney Theodore Sedgwick, the father of the writer Catherine Sedgwick. Apparently, as she served dinner to her masters, she had heard them speaking of freedom—in this case freedom from England—and she applied the concepts of equality and freedom for all to herself.

In 1781 Freeman, with the assistance of Sedgwick, initiated the case Brom and Bett v. Ashley that set a precedent for the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. According to the Massachusetts Judicial Review, the 1781 Berkshire county case of Brom and Bett v. Ashley, often referred to as the “Mum Bett” or “Elizabeth Freeman” case, was unique because it occurred less than one year after the adoption of the Massachusetts Constitution and because, in contrast to prior freedom suits, there was no claim that John Ashley, the slave owner, had violated a specific law. This case was a direct challenge to the very existence of slavery in Massachusetts.

Once free, Freeman stayed with the Sedgwick family as a servant. Sedgwick, in arguing a later case, used the example of Freeman when he said in defense of the abolition of slavery, “If there could be a practical refutation of the imagined superiority of our race to hers, the life and character of this woman would afford that refutation.”

Sarah Parker Remond (1824-1894) was an African-American lecturer, abolitionist, and agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Born of free blacks, she made her first speech against slavery when she was only sixteen years old. As a young woman, Remond delivered antislavery speeches throughout the Northeast United States. She traveled to England to gather support for the abolitionist cause in the United States. When she was older, she became a physician in Italy where she stayed until her death.

Poet and orator Frances E.W. Harper (1825-1911), the child of two free black parents, advocated for abolition and education in her speeches and publications. Her first poem collection, Forest Leaves, was published around 1845. The delivery of her public speech, “Education and the Elevation of the Colored Race,” resulted in a two-year lecture tour for the Anti-Slavery Society.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893) was the first female black newspaper editor, starting a publication titled The Provincial Freeman in Canada. Her abolitionist activities came naturally to her. Her father worked for the Liberator run by famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. After the war, Cary earned in 1883 a law degree from Howard University, making her the second African-American woman in the United States to earn this degree.

Ellen Craft (1826–1891) along with her husband William Craft (1824–1900) were slaves who escaped to the North in 1848 by traveling openly by train and steamboat, finally arriving in Philadelphia. She posed as a white male planter and he as her personal servant. The light-skinned daughter of a mulatto slave and her white master, Ellen Craft used her appearance to pass as a white man, dressing in appropriate clothing. Their daring escape was widely publicized, making them among the most famous of fugitive slaves. Abolitionists featured them in public lectures to gain support in the struggle to end the institution.

The Crafts lectured publicly about their escape. In 1860 they published a written account, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; Or, The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery . One of the most compelling of the many slave narratives published before the American Civil War, their book reached wide audiences in Great Britain and the United States. After their return to the US in 1868, the Crafts opened an agricultural school for freedman’s children in Georgia and worked the farm until 1890.

Conclusion

Thus there was far more to the abolitionist movement than just the more well-known William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, and even more than just the heroic Truth and Tubman. Many black women (as well as white women, whom I will write about next month) helped make the abolitionist movement a success. Other black women contributed to the cause of equality in the 19th century as well. In a time when women were supposed to be quiet, submissive, and apolitical; when racial prejudice was rampant in the North as well as the South; these women dared to speak out. They should not be forgotten.