William Graham Sumner on Republican Government

Sumner worried that an unaccountable elite had taken control of the American political system, hollowing out the meaning of voting and citizenship.

William Graham Sumner (1840-1910) was many things, but he was nothing if not prescient, a quality that accounts for his resurgence in intellectual discourse in the last fifty years or so. As Robert Bannister writes in a collection of Sumner essays published in 1992, Sumner was not nearly as popular in his own day as we might assume: “Far from being the Gilded Age’s most influential theorist, Sumner watched as most in his generation … largely ignored his message.” But critics always need “ogres,” to quote Banister, and after his death in 1910 Sumner would serve as a consummate ogre, the avatar for everything from corporate excess to a social Darwinist “survival of the fittest.” However, while it is incorrect to characterize Sumner as a social Darwinist—a criticism addressed by Matt Zwolinksi here—let us briefly put that debate aside as we consider his prescient commentary on republican governments. We find in this transcribed speech of Sumner’s a combination of pessimism and optimism, of what he calls “the challenge of facts” versus the promise of that which might be. It is a situation all too familiar to libertarians pushing for radical transformation but confronted by the political limits of the possible.

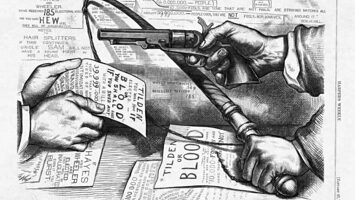

Published as “Republican Government” in 1877, this essay was first delivered as a speech upon Sumner’s return from Louisiana, where he had been investigating election fraud after the contentious presidential election of 1876. Electoral fraud in and around New Orleans was nothing new. James McPherson and James Hogue note a series of contested state and local elections throughout the 1870s, as Republicans split within their own ranks, and former Confederates began initiating the phase of Reconstruction often referred to as the Redemption period. Paramilitary violence and political chaos were common in the post-Civil War South, a region whose former Confederate soldiers and politicians felt the sting of loss and resented northern military occupation.

Thus, the stakes were high in 1876 between Republican and Civil War General Rutherford B. Hayes, and the Democrat Samuel Tilden. Tilden believed that only a Democratic victory could end the “repacities of carpet-bag tyrannies … incapacity, waste, and fraud [of Republican governments].” At the core of a possible Hayes victory was his belief that reconciliation would unite the two sections together far more effectively than the force and coercion then being employed in the South.

Events turned violent in the months leading to the election, with the “Hamburg massacre” in South Carolina leading to the execution of five black men, followed by President Grant’s reinforcement of troops in the birth place of Confederate secession. Between the violence and electoral fraud, it was unlikely that either side would accept the outcome of the election even if their opponent won fairly (a dilemma which sounds familiar to us today). Thus, Sumner was part of a federally elected group to investigate the vote returns in Louisiana, a state where two competing state governments were simultaneously operating and accusing the other of election fraud.

At the federal level, Congress appointed a bipartisan committee to officially recount electoral votes across the country but, behind closed doors, informal negotiations were already taking place. In what became known as the Compromise of 1877, the Democrats agreed to accept a Hayes victory (which was likely to be the outcome of the recount anyway), and the Hayes team agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, while also doling out federal funds and jobs to a slew of southern Democrats. Set against this backdrop of political compromise and backroom deals, it is not surprising that William Graham Sumner lost faith in the integrity of electoral politics.

Though the 1870s are seen as Sumner’s most politically active stage (he served as a New Haven alderman until 1876), his rather pessimistic essay on republican government should be seen in light of the fraud and deception that were influencing his views in real time. Sumner first draws the distinction between a republic and a democracy, though he recognizes the confusion between the two since America is typically cast as a democratic republic. Drawing on the Hamiltonian notion of a republic, Sumner defines it as “a form of self-government in which the authority of the state is conferred for limited terms upon officers designated by election.” Cutting through the high idealism of other late nineteenth-century thinkers such as John Dewey or Josiah Royce, Sumner locates the “essential institution” of republics in elections themselves (as opposed to, say, Royce’s “beloved community”). Elections are where voters express their will and, if counted honestly, this results in winners and losers with mathematical certainty; that is, we can know for sure whom the majority of ostensibly enlightened voters favored.

Such a republic can be contrasted with a popular democracy, whose goal Sumner says is a general notion of equality. Equality is only possible, he warns, in that “we can all be equally slaves together.” The language of “slavery” as the antithesis of liberty was not unintentional, and we encounter it over a century prior in the inflammatory rhetoric of pamphleteers supporting the American Revolution. For Sumner, the choice of words was even more relevant, as the recent Civil War decided the fate of chattel bondage in America. This conveys to readers, then, the seriousness with which Sumner fears a forced equality. While presumably he favors equality under the law, Sumner is opposed to it in all other realms, including political participation.

While this strikes modern sensibilities as elitist, it is actually in keeping with the Founders’ concept of a representative government. Regardless, Sumner was opposed to the “equality of slavery” that comes when republican virtue is held only by a minority, while power is held by a majority. When a government devolves into such a disparity between rights and duties, “we have an unstable political equilibrium.” Sumner was a believer in the responsibilities of republican citizenship, and for this reason, he feared a popular democracy that extended suffrage to those without such obligations. Democracies seek equality “without respect to duties,” while the aim of republics is the defense of civil liberty. Civil liberty, according to Sumner, is “the careful adjustment by which the rights of individuals and the state are reconciled with one another to allow the greatest possible development of all and of each in harmony and peace.” Regardless of the extent to which libertarians believe in the legitimacy of the state, we unavoidably live under one, and Sumner’s notion of a state that promotes peace and harmony is certainly something we can support, even if as a transitional political strategy.

Sumner is not specific about who would constitute this enlightened, responsible voting public, but he notes the exclusion of certain groups such as women, children, felons, and “idiots.” He does not take a stance on the rightness or wrongness of these exclusions, but simply points out that even in the post-Jacksonian age of wide suffrage the American republic was not all-inclusive in terms of political participation. While not necessarily a commentary on the proposed suffrage of women, or the contested suffrage of freedmen, Sumner elsewhere holds up the ideal state as one that is a “true peace-group in which there is sufficient concord and sympathy to overcome the antagonisms of nationality, race, [and] class….” And he later criticized America’s war with Spain as one essentially founded on racism; Americans could not even “assure the suffrage to negroes throughout the United States,” and yet they proposed to “liberate” Cuba. Speaking specifically about white concerns that black Americans couldn’t self-govern, Sumner wrote, “There is something ludicrous in the attitude of one community standing over another to see whether the latter is ‘fit for self-government.’” In these comments we actually glean a rather progressive stance from Sumner, at least by the standards of the time, in regards to whom he believed capable of voting responsibly.

But in general, Sumner worries about the person who wants every political right but no political duties. As he says, if the law cannot even exclude illiterate voters, what can it do? Such an irresponsible franchise in a popular democracy “cannot possibly eliminate from the ballot-boxes the error or mischief which has come into them by the votes of … incompetent persons.” We can only imagine what he might say then about elections today.

Even worse, according to Sumner, than the incompetent voter, is the trend towards mechanization of the modern voting process, where “democracy” has been even further subverted by abrogating to local pockets of power the ability to narrow political nominees. In other words, in the classic town hall—to use Sumner’s example—men might raise their hands to cast their votes, and that was that (yielding the mathematical certainty of which Sumner is so fond). But in an ever-expanding republic, indirect democracy via representation becomes a necessity, such that voters elect representatives to express their political will when it would be impractical for the entire populace to do so directly. This sounds fine in theory, and Sumner is not opposed to representation per se, but his criticism is that, by breaking-up the nomination process into a chain of irresponsible and nearly incomprehensible stages, the will of the voting public is subverted since the nominating processes are not performed by the voters themselves.

That is, candidates purported to represent the will of the voters at large are not democratically nominated; instead they are predetermined options passed down by an unaccountable minority, a product of the “smoke-filled rooms” so associated with the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. As John Stuart Mill had previously warned in Considerations on Representative Government, the danger in democracies is not necessarily the tyranny of the majority per se, but, worse, that what we see as “the majority” is actually only an influential minority; the eventual victors have already been winnowed by forces beyond the ballot box. This is precisely what Sumner fears, and is the type of mischief that comes with an unrestricted franchise where republican virtue becomes all “right” and no duty. The electoral behemoth had become so streamlined and impersonal, Sumner relates, that what counts for political participation is the man “who wants to find a ballot already printed for him, so that he can cast it in a moment or two on his way to business on election day.” This man, Sumner says, has no right to complain of bad government.

To repeat, Sumner is not opposed to voting, to elections, or to a democratic republic. Elections are the crucial institutions of free republics, he believes, and thus the polity should seek to uphold their integrity. While he admits that elections don’t produce the optimal candidates, or even the persons most amenable to the voting public, the voting process remains the best option we have: an “imperfect makeshift and practical expedient for accomplishing the end in view.” Today, however, it is not difficult to see Sumner’s fears realized when a largely irresponsible voting public exercises its power without concern for its duties and responsibilities. When elections have become so mechanized and convoluted, and just another cathartic release of political and social passions, democratic despotism creeps in through the backdoor. As Sumner warns, we don’t need an actual authoritarian Caesar to experience creeping tyranny: “There are numberless ways beside the usurpation of a dictator in which civil liberty may be lost.” The only counter to the erosion of civil liberties, in his view, is the “jealous instinct of the people.”

I am confident that Americans are jealous, but I am much less confident that their jealousy is for civil liberty. What passes today for a democracy is certainly not the republic of the Founders, or of William Graham Sumner a century later; whatever it is that we have today is hardly democratic at all. It is a duopoly that uses undemocratic means to foist a minority of predetermined candidates on a largely shortsighted public. Like Sumner feared, we cast our preprinted ballots in a moment or two on the way to work and pat ourselves on the back as if wearing an “I voted” sticker qualifies us as responsible citizens. But for us, as for Sumner, there is hope in pursuing the ideal of both rights and duties. One without the other results in the unstable political equilibrium of which he warned. We must do away with the idea of “saviors of society,” to quote Sumner: “The constitutional republic … does not call upon men to play the hero; it only calls upon them to do other duty [sic] under the laws and the constitution, in any position in which they may be placed, and no more.”