Rose Wilder Lane on Islam and American Values

Rose Wilder Lane saw the establishment of Islam and the American Revolution as two leaps forward for liberty.

Poll after poll has shown that a large portion of Americans fear the religion of Islam and its followers. Of course, some might argue that there is a reasonable basis for this prejudice and that this fear might even be rational due to harrowing terrorist attacks such as the tragic events of 9/11. So, are terrorist attacks what really drives this fear of Muslims?

An opinion poll conducted three weeks after 9/11 by ABC found 47% of Americans held favorable views on Islam while 39% held unfavorable opinions. A decade later, a similar opinion poll, conducted by the Brookings Institute, found that attitudes had changed. According to Shibley Telhami’s research, by 2011, only 33% of Americans expressed favorable views of Islam, while 61% stated an unfavorable opinion. In short, today, Americans are more afraid of Muslims and Islam than directly after 9/11.

Researchers who surveyed Americans following the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris and San Bernardino found these attacks had little effect on Americans’ attitudes towards Muslims. In fact, what is mainly driving increasingly anti-Muslim sentiment is the idea that Islam is a religion fundamentally incompatible with American values.

One American author who had a deep understanding of both the American and Muslim worlds was the famous 20th-century author Rose Wilder Lane. What did she say about these two apparently discordant civilizations? In contrast with contemporary conservatives, Lane saw an affinity between Islamic civilization at its best and America.

Today, Rose Wilder Lane’s literary fame has been eclipsed by her mother, Laura Ingalls Wilder, the author of the wildly successful Little House on the Prairie books which have been adapted for stage productions, tv shows, and even a Japanese anime. But during the first half of the 20th-century, Lane was a famous journalist and writer. Lane was an iconoclast, defending individualism and laissez-faire at a time when the intellectual class was fixated on authoritarian statist ideologies like fascism and socialism. However, Lane herself had once been a socialist and even flirted with joining the Communist Party. But after visiting the USSR as a reporter for the Red Cross, she realized that centralized government power and a state-run economy really meant a state-run populace.

Returning from the USSR, Lane wrote, “Like all Americans, I took for granted the individual liberty to which I had been born. It seemed as necessary and as inevitable as the air I breathed; it seemed the natural element in which human beings lived.” Lane now understood that freedom is a fragile gift always in danger. So she began her lifelong crusade to protect individualism from all threats.

Careful readers can spot Lane’s emphasis on individualism in the Little House book series. We now know that Lane took an active hand in co-writing the series even if her mother received the sole credit as author. As a former socialist turned American individualist and the co-author of a series embodying the pioneer spirit of America, Lane’s views on the compatibility of Islam and America should hold significant weight on the debate over whether or not Islamic values are fundamentally anti-American.

Among libertarians, Rose Wilder Lane is best known as one of three founding women who established the libertarian movement (a phrase Lane herself coined). In 1943, Lane published The Discovery of Freedom. In this book, she tackles the question of why the majority of humanity throughout history lived in grinding poverty in a stark contrast to the explosion of prosperity during and after the Enlightenment. Lane’s answer was the title of the book, The Discovery of Freedom. Traditionally, history consists of the study of supposedly “great men,” but Lane focused instead on the prosperity of ordinary folk. Lane made ordinary folk the centre of her analysis. She wanted to see how their lives improved and by what means, her answer was freedom, a potent yet fragile ideal.

Lane believed that there were three notable attempts at establishing a free society. The first was undertaken by the Biblical figure Abraham. Abraham might seem like an odd place to start with the story of freedom, but Lane argued that Abraham’s monotheistic beliefs had liberatory effects. Abraham lived amongst polytheists who believed every aspect of the world was controlled by various and capricious Gods. Since every single aspect of life was decided by invisible forces beyond human control, these polytheists believed their fate was not in their own hands. They were merely along for the ride as the Gods either granted blessing or wreaked havoc on their lives. Abraham contradicted this deterministic view when he proclaimed there is only one God. Rather than control humans, the Hebrew God gave them the unique gift of free will. As a result, they bear the consequences of their actions in this life and in the next life. Lane admired Abraham because he raised awareness of the human condition and human agency. At a fundamental level, freedom requires the ability to choose.

Being patriotic, Lane listed the third and most recent attempt at a free society as the American Revolution, some three thousand years after the death of Abraham. But what happened in between? Contra many scholars both ancient and modern, Lane skips over democratic Athens and republican Rome as she traces the lineage of modern freedom. Instead, Lane cites the establishment of Islam as the second great attempt to create a free society, drawing many parallels between American society and the peak of Islamic civilization.

With the fall of the Roman empire, Europe receded into the Dark Ages; Lane argues that during this time, the thriving and modern cities were all located in the east, places like Baghdad, Damascus, Antioch, and Alexandria. The prophet Muhammad was born into this world. Lane describes him as a “self-made businessman” born in poverty, but who, through hard work, became a successful man, “widely known and well respected.”

Like Abraham, Muhammad lived in a polytheist society and, akin to Abraham, he believed there was only one God, and God does not control humans, they are able to practice free will. Powerful polytheists opposed Muhammad, but he did not flinch. According to Lane, Muhammad said, “There is no kind of superior man; men are humanly equal.” Here Lane is paraphrasing Muhammad’s “Farewell Sermon”: “An Arab has no superiority, over a non-Arab nor a non-Arab over an Arab; neither does a white man possess any superiority over a black man, nor a black man over a white one, except by virtue of piety.” Muhammad prohibited any intermediaries such as priests or bishops that stand between individuals and God. Lane wrote that because of this “each individual must recognize his direct relation to God, his self-controlling, personal responsibility.” Muhammad’s message of egalitarianism attracted so-called “undesirables” to Islam, people who hailed from less influential tribes and slaves who saw the emancipatory value of Islam.

Persecuted for his beliefs, Muhammad and his followers were forced to flee from Mecca and take refugee in Medina. Though Medina was subsequently attacked, Muhammad and his followers rebuffed their attackers with ease through an ingenious form of trench warfare. After spending six years in Medina, Muhammad and his followers went on a peaceful pilgrimage to Mecca and the former polytheists began to accept Muhammad’s beliefs. Like Abraham before him, Muhammad declared that all men are free, that there is one God, and that he does not control humanity. Over the next eighty years, Islam spread at a speed that later observers could barely comprehend. As Islam spread, Lane believes the knowledge of mankind’s right to freedom was ingrained in people’s minds from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic. Muhammad’s radical idea of humanity as fundamentally free in nature brought with it what Lane calls, “The first great creative effort of human energy. It created the first scientific civilization.”

While Europe experienced widespread stagnation during what has often been dubbed the Dark Ages, Lane believed “the world was actually bright with an energetic, brilliant civilization, more akin to American civilization.” Lane pointed out that in American schools and academia, the history of the Middle East in this period is largely ignored or marginalized, a trend that sadly persists today.

The period that Lane discusses spanned from the 8th to the 14th-century and is dubbed by scholars the “Islamic Golden Age,” a period of cultural, economic, and, perhaps most importantly, scientific flourishing in the Islamic world. For Lane, a scientific approach is what separated Americans from their European ancestors. It is also what made the Americans and the people of the Islamic Golden Age kindred spirits in Lane’s eyes.

According to Lane, Americans’ European ancestry--with their strict hierarchies and religious wars--did not endure and has not influenced today’s descendants. What most alienated Lane was that medieval “Europeans whole world rested upon the pagan belief that Authority controls all things including men.” The American dynamism, individualism, and freedom that Lane admired was severely lacking in medieval Europe but found in abundance throughout the Middle East. Lane acknowledged that this explosion of creativity was not solely experienced or created by Muslims, and, in fact, “these men were of all races and colors and classes… by no means all of them were Muslims.” To avoid confusion, she collectively groups anyone living during this period of progress as a “Saracen”, a term first popularized by bewildered European observers who could scarcely keep track of the diverse demographics of these foreign lands. Though this term is outdated (and at times offensive) today, it was the best Lane could think of to denote the massive variety of peoples living in the Middle East.

During this Golden Age, Lane notes, Muslims established the first-ever universities, such as the University of Cairo, which has now existed for more than a thousand years. But even more impressive to Lane is that these universities had no curriculum, no degrees, and no exams. She stresses that these universities were institutions of learning, not of teaching, thus students were allowed the greatest freedom possible to attend what classes or lectures they thought best suited their needs.

A thousand years later, Thomas Jefferson would, when establishing the University of Virginia, follow similar practices in education. He wrote gleefully, “We shall allow them (students) uncontrolled choice in the lectures they choose to attend.” Both of these approaches were alien to the strict top down approach of traditional European Universities, which were equipped with hierarchical, top-down approaches to education.

Lane observes that before the “Saracen’s” ascent, the much esteemed ancient Greeks and Romans used clunky systems of numbers that required an abacus to perform even the most basic arithmetic. With a newfound appreciation of a universalized approach to knowledge, the “Saracens” appropriated Hindu numerals and turned them into the Arabic numerals we use to this day.

But the “Saracens” also innovated. They created the number zero. While this might sound like a pretty innocuous achievement, Lane believed it was the key to modernity. She explains at length, “Any mathematician will tell you, without zero, there could not be mathematics” and that “without zero, Americans would have no engineering, no chemistry, no astronomy, no measurement of substance or space. Without zero, there could not be a skyscraper, a subway, a modern bridge or highway, a car, an airplane, a radio, a city water supply, or rayon or cellophane or aluminum or stainless steel or a permanent wave.”

Lane is not fully factually correct here, although her broad point stands.The first recorded use of the number zero appeared in Mesopotamia much earlier in the 3rd-century BC. Indian thinkers in the fifth-century AD did spread zero to surrounding countries, which eventually reached the Muslim world by the eighth-century. Through contact with Muslims, Europeans finally adopted the number zero by the 12th-century. While the “Saracens” did not invent zero, they did transmit it to the European world and are responsible for the subsequent mathematical revolution.

The “Saracen” advances in mathematics were applied with great effect to astronomy and navigation. Without “Saracen” innovations such as the sextant, the magnetic compass, and portolani charts, it is doubtful the age of exploration or the discovery of America would have occurred. Thus, without the Muslim world, there would be no America as we know it today.

The next achievement of the “Saracens” that Lane lists is that “they also did more than anyone else to make Americans healthy.” Lane argues that long before anyone even stepped foot on the Mayflower, “Saracens” from the “Ganges to the Atlantic” built numerous hospitals and medical institutions. Lane observes that while European physicians were bloodletting, using leeches, and praying to heal the sick, the “Saracens” “were using the entire American medical pharmacopeia of today” including local anesthesia.

But Lane did not reserve her admiration solely for medical and scientific discoveries. She talks at length about how the “Saracens” were responsible for inventing many everyday objects that contribute to our comfort and ease of life, such as bed linens, makeup, oil lamps, carpets, cushions, and even ice cream. She reminds her readers that whenever Americans say the words for mattress, sofa, cotton, talcum, sugar, coffee, sherbert, or benzine, they are unwittingly speaking Arabic, as these inventions and the names for them all originated from the east. Despite the average American knowing little about the Islamic Golden Age, Rose remarks, “Our cars run, our streets are paved, our houses are furnished and our bodies clothed with things that the Saracens created.”

Lane proves that if Europe never interacted with Muslim civilization, our lives would be poorer, rougher, and less beautiful. She constantly illustrates how America has not only benefited from the legacy of this era, but also shares similar fundamental values and principles. America and the civilization of the Islamic Golden Age look most similar in their approach to multiculturalism and pluralism. During the Islamic Golden Age, peoples from across the known world--Hindus, Mongols, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Armenians, Jews, Persians, Medes, Arabs, Greeks, Egyptians, Phoenicians, Hittites, and many more--all lived together in relative harmony. A thousand years later and across an ocean, Spanish, Norwegian, Dutch, Germans, French, Irish, Scots, and Swedes, in a similar manner, cooperate regardless of their religious and cultural differences. “In both cases,” Lane writes, it was as if one spark had landed on gunpowder and created “a terrific outburst of human energy.”

Despite being separated by a thousand years and thousands of miles, both civilizations in Lane’s opinion share four important features. Both embrace a scientific approach to problems, experimenting and constantly increasing their pool of knowledge. Second, their essential function is the distribution of goods and the subsequent increase of comfort and pleasure. War, on the other hand, is unprofitable, it is to be avoided. Third, a humane ethos of tolerance towards all races and creeds prevails leading to peace. And lastly, both have standards of living, health, cleanliness, and comfort that increase rapidly and continuously. After listing these qualities, Lane writes, “Saracens created that kind of civilization. Americans are creating that kind of civilization.”

Conservative Americans might protest at the idea of America being compared to the Golden Age of Islam. Still, Rose Wilder Lane understood this was not an insult but a great compliment. It is saddening that today Islam, under the influence of a small yet concentrated cadre of extremists, is in dire need of reform. The narrative we often hear labels Islam as barbarous, backward or uncivilized is incorrect. But worse yet, it will only push the disaffected further into extremist margins.

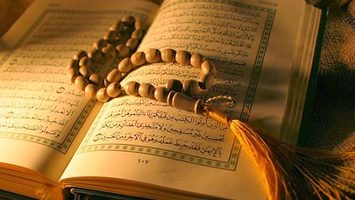

Instead, we ought to celebrate humane Islamic thinkers such as Ibn Rushd, support those who fight for reforms, and above all else, respect the first amendment and the Founders’ ideal of religious freedom. After all, Thomas Jefferson, an ardent defender of religious liberty, owned and studied the Quran while defending religious liberty not only for various forms of Christianity but also for followers of Islam. I often hear critics of Islam ask, “what has Islam to offer the world?” Eighty years ago, Rose Wilder Lane offered a comprehensive answer to this question. She illustrated that both the America Revolution and the Golden Age of Islam pushed towards the hallowed liberal principle that all people are born free and equal.