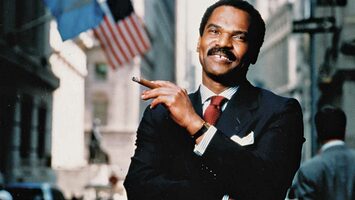

Reginald Lewis, America’s First Black Billionaire

Lewis broke through a number of glass ceilings to become a successful lawyer, businessman, and philanthropist.

Although prior Black entrepreneurs had amassed large fortunes, Reginald F. Lewis was the first Black American to build a billion-dollar company. Embodying self-reliance, Lewis’ business acumen and meteoric rise in fortune was achieved without the benefit of either inherited wealth or familial connections.

Born in 1942 in Baltimore, Maryland, where he was also raised, Lewis graduated with a degree in political science from Virginia State University, a historical black college.

In 1965, he was among a select number of black students chosen for a summer school program at Harvard Law School. He was later invited to attend there, becoming the only student in the long history of the school to be admitted prior to applying.

After completing law school, Lewis established his own practice, Wall Street’s first black-owned law firm. After working 15 years as a corporate lawyer, Lewis established a venture capital firm known as TLC Group L.P. Through TLC he negotiated his first significant business deal, the $22.5 million purchase of the home sewing pattern business McCall Pattern Company. He later steered the company to two of its most profitable years ever.

In 1987, Lewis led a leveraged buyout of the food, beverage, and grocery store conglomerate Beatrice Foods for $985 million, giving it the distinction of being the largest black owned and managed business in the nation at that time. Renamed TLC Beatrice International, the company--which encompassed 64 companies in 31 countries--grew into a multinational powerhouse.

By the late eighties, Lewis had become one of the richest Black Americans and was listed among the Forbes 400.

Lewis’ college classmate and close friend Lin Hart, who authored the biography Reginald F. Lewis Before TLC Beatrice: The Young Man Before The Billion-Dollar Empire, had this to say about his late friend:

While uniquely gifted, Reginald’s critical trait, however, was a sustainable belief in the eventuality of his success. He never doubted for a minute that he was going to succeed. Whenever Reginald said that he was going to achieve something you could count on him making that happen. Whether it was running through a wall or whatever, somehow he was going to find a way to make that happen.

Lewis’ own account of his life can be found in “Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun,” edited by Blair S. Walker just prior to Lewis’ death in January 1993. Walker said during a 2020 interview with the author:

I’m originally from Baltimore just like Reginald Lewis was and attended public school there. I started out as a copy boy with the Baltimore Sun while I was still in high school. After college, I got my first job down in Florida with a newspaper. I worked in the news media for a number of years, with stints at the Associated Press in Chicago and New York News Day. My last stop was at USA Today.

While at USA Today, Walker received a news wire alert informing him that Reginald Lewis was in a coma:

It became clear to me then that he was in very bad shape. So I asked my editor if it would be ok if I wrote an appreciation on Reginald Lewis and his life accomplishments upon his death. And my editor gave me the green light.

After Reginald passed away on January 19, 1993, Walker said of him:

I never met him nor had a face to face sit-down but was always interested in him. Since I was a business reporter with USA Today, I felt that someone needed to write a book about Lewis. So after some thought, it became clear to me that I needed to write that book even though I had never written one before.

Asked how the book’s title, Why Should White Guys Have All The Fun, originated, Walker said:

That title came from a conversation that took place when he was a little boy. He must have been about seven or eight and his grandparents were giving him a bath. They were discussing employment discrimination which was occurring in Baltimore amid the throes of Jim Crow back in the 40’s. During the course of that conversation, the question was posed as to whether things were going to be any different for Reginald when he became a grown man. Reginald on hearing this said, ‘sure.’ ‘Why should white guys have all the fun?

Walker said that this comment from Lewis was early evidence of his desire to do extraordinary things.

He was going to go where few people had gone before, black or white. And he wasn’t going to be held back by impediments.

On his journey to the top, Walker asserted that Lewis was always “one to play by the rules and do things correctly, avoiding cutting corners or cheating. Being that he was a black man, he knew that there were eyes on him at all times. He believed that one had to pay their dues to succeed and not cut corners.”

Walker cited Lewis’ spectacular $3.6 million summer home in trendy East Hampton, on New York’s Long Island, as one indicator of his unparalleled rise as a black man in the late twentieth century. He noted that Lewis was also quite the philanthropist, having established the Reginald F. Lewis Foundation, which sent millions of dollars in grants to various non-profit programs and organizations. Sadly, Lewis died in 1993 at the age of 50 from brain cancer.

In a concluding thought, Walker had this to say about Lewis’ legacy:

Writing this book has been a most satisfying experience. I’ve been approached by innumerable African-American entrepreneurs who have said that they have used the book as their personal bible, noting that Reginald’s “the sky’s the limit” mentality inspired them.