Lord Acton’s History of Liberty and Its Higher End

For Lord Acton, the foundation of liberty was the individual conscience, which holds each of us accountable to a higher law.

In his own time Lord Acton (1834-1902) was reputed to be the most learned man in England, if not all of Europe. Two years after his death, a member of parliament memorialized Acton as “one of the most remarkable and most peculiar figures in the generation which is now beginning to pass away” (Bryce 1904, 698).

Acton is often remembered for a number of famous quotations. Among them is the following: “Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end” (Acton 2017, 21). Many have understood this to mean that liberty as such is the consummation of human flourishing. But that could only be true if politics were the most important aspect of human existence. Liberty is man’s highest political end, but politics is not the highest end of man.

As Acton writes a bit later in that same section, “Liberty is not the sum or the substitute of all the things men ought to live for” (Acton 2017, 21). For Acton, the history of freedom is the narrative of the human discovery of and respect for the necessity of the liberty of conscience before God—and thus before man as well.

Acton had a keen intellect coupled with an appetite for ever more knowledge (and books). Acton’s enduring passion was to explore the idea of liberty as a historical phenomenon through the lens of his commitment to a transcendent moral order. This moral-historical approach, for which Acton was to become both famous and maligned, required not only a rich understanding of chronology, events, figures, and movements, but also a vivid intellect able to parse nuances in theology, philosophy, law, politics, and economics.

Acton was an accomplished essayist and correspondent, evident from his relationships, epistolary and otherwise with William Gladstone as well as his daughter Mary, and Bishop Mandell Creighton among others, as well as his contributions to The Rambler, where he succeeded John Henry Newman as editor. But his defining calling was that of the historian. Alas, Acton’s magnum opus was never to come to fruition. Acton’s scholarly reach exceeded even his remarkable intellectual grasp. It is a testament to Acton’s abilities, however, that even the barest sketch of his proposed history of liberty, in two lectures delivered in 1877, have won him renown and attention into the third millennium of what Acton would call the “Christian era.”

In his addresses on “The History of Freedom in Antiquity” and “The History of Freedom in Christianity” Acton traces a variety of dynamics across the centuries. He is concerned with the ideas of liberty and how they relate to the historical contexts and institutions of different times. He distinguishes liberty from tyranny, authority, order, government, and license. He strives to trace out the interrelationships between reason and tradition, law and will, centralization and federalism, absolutism and limited government, as well as stability and change. Throughout these lectures Acton works with a definition of liberty focused on the primacy of the individual conscience. Liberty, he says, is “the assurance that every man shall be protected in doing what he believes his duty against the influence of authority and majorities, custom and opinion” (Acton 2017, 3).

Nearly two decades earlier Acton had defined liberty in terms of the Roman Catholic conception, which he distinguished from the modern understanding. Liberty, he said, is not “the power of doing what we like, but the right of being able to do what we ought” (Acton 1860, 146). Duty and moral obligation, grounded in transcendent truth, are in this way foundational for Acton’s analysis of liberty in history, an analysis he opens by tracing the ideas and institutions of the ancient world.

Freedom in Antiquity

To speak of freedom in antiquity is, for Acton, in some ways a futile exercise. The basic picture Acton sketches of the ancient world is one characterized by tyranny, force, and centralization. “In ancient times,” says Acton, “the State absorbed authorities not its own, and intruded on the domain of personal freedom” (Acton 2017, 4). Indeed, contends Acton, “Six hundred years before the birth of Christ absolutism held unbounded sway” (Acton 2017, 6).

But if we look at the level of principle and examine the ideas of the ancient world rather than the realities of political power and coercion, the verdict is rather more nuanced. The ancient world, particularly in the wisdom of Greek philosophy, had discovered and articulated the ideas of liberty. When looking particularly at the ancient Teutons as well as the Greeks, Acton argues that “we discover germs which favouring circumstances and assiduous culture might have developed into free societies” (Acton 2017, 5).

Indeed, there are by Acton’s account some particularly praiseworthy moments in ancient history. Foremost for Acton is Solon’s constitutional revolution among the Greeks in the sixth century BC. “By making every citizen the guardian of his own interest,” argues Acton, “Solon admitted the element of Democracy into the State” (Acton 2017, 7). And by doing so a fundamental element of enduring political liberty was actualized. The people, now endowed with political rights as well as legal liberties, were agents of moral suasion and discourse rather than simply pawns in the power politics of great men.

Solon’s system “introduced the idea that a man ought to have a voice in selecting those to whose rectitude and wisdom he is compelled to trust his fortune, his family, and his life.” Such a conception was transformative, as “this idea completely inverted the notion of human authority, for it inaugurated the reign of moral influence where all political power had depended on moral force. Government by consent superseded government by compulsion, and the pyramid which had stood on a point was made to stand upon its base” (Acton 2017, 7).

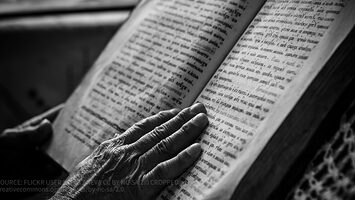

The ancient Hebrews too had realized some essential institutions of freedom. The political structure of ancient Israel amounted to a human monarchy limited by a constitution instituted and delimited by divine covenant. Acton notes that Israel was not originally a monarchy at all, but a federation, and when the Israelites finally were given a king, “The throne was erected on a compact; and the king was deprived of the right of legislation among a people that recognised no lawgiver but God, whose highest aim in politics was to restore the original purity of the constitution, and to make its government conform to the ideal type that was hallowed by the sanctions of heaven” (Acton 2017, 4).

In his brief survey of liberty among the Israelites, Acton describes the essential characteristics of free societies. Israel manifested the two basic dynamics by which “all freedom has been won—the doctrine of national tradition and the doctrine of the higher law.” The Israelite polity recognized “the principle that a constitution grows from a root, by process of development, and not of essential change; and the principle that all political authorities must be tested and reformed according to a code which was not made by man” (Acton 2017, 4-5). The historical narratives and prophetic rebukes recounted in the Hebrew scriptures, however, describe the idolatry, corruption, exile, and dissolution of the kingdoms of Judah and Israel.

In diaspora and into the time of Christ the Hebrews endured as a people under the Roman imperium. The emergence of freedom among the Greeks under Solon was succeeded by the dissolution of liberty after Pericles. “Parallel with the rise and fall of Athenian freedom,” says Acton, “Rome was employed in working out the same problems, with greater constructive sense, and greater temporary success, but ending at last in a far more terrible catastrophe” (Acton 2017, 12).

The Greeks were characterized by their commitment to reason, even when that reason dissolved inherited customs. By contrast, the Romans were more practical and committed to tradition. Acton contrasts the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, acknowledging that there are ebbs and flows of liberty in each epoch. On Acton’s account, the ultimate conclusion of the history of liberty in antiquity, however, is that of futility and exhaustion.

For Acton, the pagan world had blossomed and manifested its awesome and terrifying potential but ended in decadence and decay. He evaluates the ancient world in terms of both ideas and institutions, and concludes that if “we should form our judgment of the politics of antiquity by its actual legislation, our estimate would be low” (Acton 2017, 15). The concrete realities of the ancient world were characterized by absolutism, tyranny, and arbitrary power, as “rights secured by equal laws and by sharing power existed nowhere” (Acton 2017, 6).

However, the ancient ideas of liberty, discovered by the Greeks and cultivated by the Romans, were waiting for a catalyzing force to bring them to a higher plane and manifest them in a more perfect way. The history of freedom in antiquity ends on this rather bleak note, pointing forward to the advent of Christ: “The liberties of the ancient nations were crushed beneath a hopeless and inevitable despotism, and their vitality was spent, when the new power came forth from Galilee, giving what was wanting to the efficacy of human knowledge to redeem societies as well as men” (Acton 2017, 25).

Freedom in Christianity

In the ancient world, Acton says, “Morality was undistinguished from religion and politics from morals; and in religion, morality, and politics there was only one legislator and one authority” (Acton 2017, 15). But the ideas of freedom discovered and refined in antiquity provided conditions for the greater future realization of liberty.

The transition from antiquity to modernity, or in Acton’s parlance from antiquity to “Christianity,” is in many ways an account of the positive reception and refinement of ancient ideas. Acton describes “the energies of the Greek intellect” as “the grandest movement in the profane annals of mankind,” and contends that we owe to the ancient world “much of our philosophy and far the better part of the political knowledge we possess” (Acton 2017, 8). He also suggests that “The best of the later classics speak almost the language of Christianity, and they border on its spirit” (Acton 2017, 24).

The social transformation brought forth by Christianity was made possible by its affirmation of diverse social authorities, a stark difference from the absolutism characteristic of antiquity. This diversity was worked out historically in the contest for primacy between church and state. The actual enjoyment of liberty arises out of this conflict, just as tyranny arises from the centralization of power.

Christ’s teachings about the civil authority and its relationship to the church are transformative. In one of his more memorable passages, Acton lauds the dawning of a new era of liberty with the coming of Christ:

When Christ said: “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s,” those words, spoken on His last visit to the Temple, three days before His death, gave to the civil power, under the protection of conscience, a sacredness it had never enjoyed, and bounds it had never acknowledged; and they were the repudiation of absolutism and the inauguration of freedom. (Acton 2017, 27)

Despite Acton’s praise of the accomplishments of the ancient world—the philosophy of the Greeks, the laws of the Romans, and the covenantal polity of the Hebrews—it is only with Christ’s coming that the world enjoys “the inauguration of freedom.” In this way the enjoyment of political freedom in the context of social institutions depends on a prior spiritual freedom. Christ’s dictum gave both sanction and limit to civil political power and placed that power under a higher authority: God. The demands of worldly political power could never justly transgress that prior, vertical relationship between the individual and God.

Acton works through the travails of liberty over against tyranny throughout all of history, and tyranny is in fact characterized by the centralization of power in any institution or sphere, whether church or state. The history of freedom in Christianity is far from a straightforward march of progressive freedom through the ages. For Acton, despite (or perhaps on account of) his religious convictions, the church, as it seeks worldly preeminence, becomes as much a danger to liberty as the coercive state.

Lord Acton’s most famous saying is, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” (Acton 1887, 383). The context of this wise assertion is related to claims of authority by the Roman pontiff rather than civil rulers, kings, or emperors. The medieval period saw the initial corruption of the church as it wedded itself too closely to political power or in fact sought to make civil authorities subservient to ecclesiastical interests: “Christianity, which in earlier times had addressed itself to the masses, and relied on the principle of liberty, now made its appeal to the rulers, and threw its mighty influence into the scale of authority” (Acton 2017, 32).

With characteristic pithiness, Acton continues his analysis of the ideas of liberty as they relate to the realities of political institutions, and as he traces the history into the age of the Renaissance and Reformation he bemoans the domination by a sophisticated kratocracy (rule by the most powerful) and the domestication of morality to the interests of politicians: “All through the religious conflict policy kept the upper hand. When the last of the Reformers died, religion, instead of emancipating the nations, had become an excuse for the criminal art of despots. Calvin preached and Bellarmine lectured, but Machiavelli reigned” (Acton 2017, 42).

Even so, the institutional conflicts between church and state, and the increasingly diverse social environment including guilds, corporations, academies, monasteries, and religious orders paved the way for advances of liberty. Authority in a wide variety of spheres was validated by Christian teaching, and along with that plurality of authority and social power came freedom. Out of the religious war across Europe, a foundational insight was finally affirmed and instituted: “The idea that religious liberty is the generating principle of civil, and that civil liberty is the necessary condition of religious, was a discovery reserved for the seventeenth century” (Acton 2017, 50). The spiritual freedom that Christ’s teaching valorized provided the conditions for social diversification, institutional limitations on civil and religious authorities, and something approaching a stable equilibrium and peace.

The Moral Basis for Liberty

Acton continued the narrative from the seventeenth century to his own day and his own land in England. He observes, “That great political idea, sanctifying freedom and consecrating it to God, teaching men to treasure the liberties of others as their own, and to defend them for the love of justice and charity more than as a claim of right, has been the soul of what is great and good in the progress of the last two hundred years” (Acton 2017, 50).

Acton’s history of liberty is a history of the liberty of the minority against the majority, the recognition that there are some lines that can never be justly crossed and some rights that can never be overruled. “It is bad to be oppressed by a minority,” writes Acton, “but it is worse to be oppressed by a majority” (Acton 2017, 11). The smallest minority in a society is the individual, and the center of the individual for Acton is the conscience, the moral sense that holds a person accountable to God. Freedom of conscience is therefore the moral basis for liberty. As Acton relates, “True freedom, says the most eloquent of the Stoics, consists in obeying God” (Acton 2017, 23), and a person knows what God requires primarily through their individual convictions formed by their conscience.

If the individual’s moral sense is the foundation for liberty, then it is proper for the political order to be oriented towards respecting that sense and acknowledging that religion and civil society are structured to form and inform the conscience. In this way Acton’s liberalism is grounded in a commitment to transcendent truths and higher things, most importantly the moral law and the divine lawgiver—to whom all are equally accountable.

Works Cited

Acton, John Emerich Edward Dalberg. 1860. “The Roman Question.” The Rambler n.s. 2.5(January): pp. 137-154.

Acton, John Emerich Edward Dalberg. 1887. “Acton-Creighton Correspondence.” In Essays in the Study and Writing of History, edited by J. Rufus Fears, pp. 378-391. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund [1986].

Acton, John Emerich Edward Dalberg. 2017. Lord Acton: Historical and Moral Essays. Edited by Daniel Hugger. Grand Rapids: Acton Institute.

Bryce, James. 1904. “The Letters of Lord Acton.” The North American Review 178.570(May): pp. 698-710.